„Value is … the importance that individual goods or quantities of goods attain for us because we are conscious of being dependent on command of them for the satisfaction of our needs.”1

The concept of “value” is the core element of a general theory of human behavior, it transcends the traditional confines of economic science.

Value is a subjective concept – which means: value lies in the eyes of the beholder; there is no such thing as “objective value”.

Goods or things (books, apples, computers, etc.) do not have value per se. It is always the individual that assigns value to them (or not).

Value is not an artificially invented concept. Rather, it is a category of human action, it is a praxeological (or: a logic of human action) concept.

Human action means, generally speaking, replacing one state of affairs with another state of affairs, expected to be more beneficial to the actor.

It is a primordial fact that humans act.

And the statement “Humans act” cannot be denied without causing a logical contradiction, that is saying something false.

The statement “Humans act” is apodictically true, it is an a priori (in the Kantian sense): The denial of an a priori statements presupposes its validity.

If you say something like “Come on, humans do not act”, then you act, proving the truth of the very statement you wish to deny.

From the apodictically true statement “Humans act”, we can deduce further true statements.

For instance, human action implies that an actor’s behavior is purposive, it is directed toward goals. Again, this statement cannot be denied without causing a logical contradiction.

An actor must employ means to achieve his ends. Action without means is logically impossible to think.

Human action implies that the actor has consciously chosen certain means to reach his goals.

And since the actor wishes to attain these goals (whatever they may be), they must be valuable to him; and accordingly, he must have values that govern his choices.

What is more, every goal of human action must be considered worth more to the actor than its cost and capable of yielding a profit (a result whose value is ranked higher than that of the foregone opportunity).

And that every action is also invariably threatened by the possibility of a loss if an actor finds in retrospect that contrary to his expectations the actually achieved result has a lower value than the relinquished alternative would have had.

To reiterate, value is a praxeological concept, and this statement cannot be disputed without causing a logical contradiction (and thus saying something false).

Against this backdrop it is easy to understand what happens in a voluntary exchange. Consider the case in which you buy, say, 1 Krugerrand for 3.000 US-dollar per ounce at your favoured coin shop, run by Mr Rich.

In such a transaction you surrender something you consider less valuable (3.000 US-dollar) against something you value more highly (1 Krugerrand).

Likewise, in the exchange Mr Rich receives something he values more highly (3.000 US-dollar) against surrendering something (1 Krugerrand) he values less highly.

The voluntary exchange benefits you as well as Mr Rich. It is not a zero-sum game (that is, one person benefitting at the expense of another). On the contrary!

The voluntary exchange is beneficial to both parties involved, thus increasing their state of want satisfaction – compared to a situation without the voluntary exchange having taken place.

It should be highlighted that the voluntary exchange did not take place because of harmonious wishes on your and Mr Rich’s side. It took place because of opposite value scales: You wanted 1 Krugerrand in exchange for your 3.000 US-dollar, while Mr Rich wanted 3.000 US-dollar in exchange for 1 Krugerrand.

The voluntary exchange led to a peaceful and mutually beneficial outcome. Isn’t that wonderful?

Let us address the issue of ´value´ and ´utility´ in some more detail.

You assign value to things because you derive so-called utility from them (by owning them, seeing them, touching them, eating them etc).

Value and utility cannot be measured.

You can measure, say, a distance in meters or miles, or a weight in grams or pounds, or a temperature in Celsius or Fahrenheit. For these cases we deal with extensive magnitudes – and they are open to cardinal numbers.

Value and utility, however, are not extensive, but intensive magnitudes. They can only be conceptualized in ordinal terms (but not in cardinal terms) like “more is better than less” or “I like A more than B”.

An actor assigning value to things (and deriving utility from it) means is that he ranks them on a ‘value scale’.

All an actor can say is “I like A more than B”, or “I like C less than D”. He cannot say “I like A two times more than B” or “I like C five times less than D”. To say so would be meaningless.

What is more, the subjective value cannot be compared among different people.

As noted earlier, value and the associated utility cannot be measured, they can only be ranked on an individual’s ordinal scale.

In this context it is important to remind ourselves of the law of diminishing marginal utility (which can also be derived from the logic of human action – and is thus also an a priori).

What does the law of diminishing marginal utility say? Murray N. Rothbard (1926–1995) explains:

“There are … two laws of utility, both following from the apodictic conditions of human action: first, that given the size of a unit of a good, the (marginal) utility of each unit decreases as the supply of units increases; second, that the (marginal) utility of a larger-sized unit is greater than the (marginal) utility of a smaller-sized unit. The first is the law of diminishing marginal utility. The second has been called the law of increasing total utility. The relationship between the two laws and between the items considered in both is purely one of rank, i.e., ordinal.”

To illustrate Rothard’s explanation of the law of diminishing marginal utility, consider the following value scale of an actor (say, Mr Schulz):

Ranks in Value2

3 eggs

2 eggs

1 egg

2nd egg

3rd egg.

The higher the ranking on this individual value scale for eggs is, the higher is the value. By the second law, 3 eggs are valued more highly than 2 eggs, and 2 eggs are more highly than 1 egg.

By the first law, the 2nd egg will be ranked below the first egg on the value scale3, and the 3rd egg below the 2nd egg.

No mathematical relationship exists between, for instance, the marginal utility of 3 eggs and the marginal utility of the 3rd egg except that the former is greater than the latter.

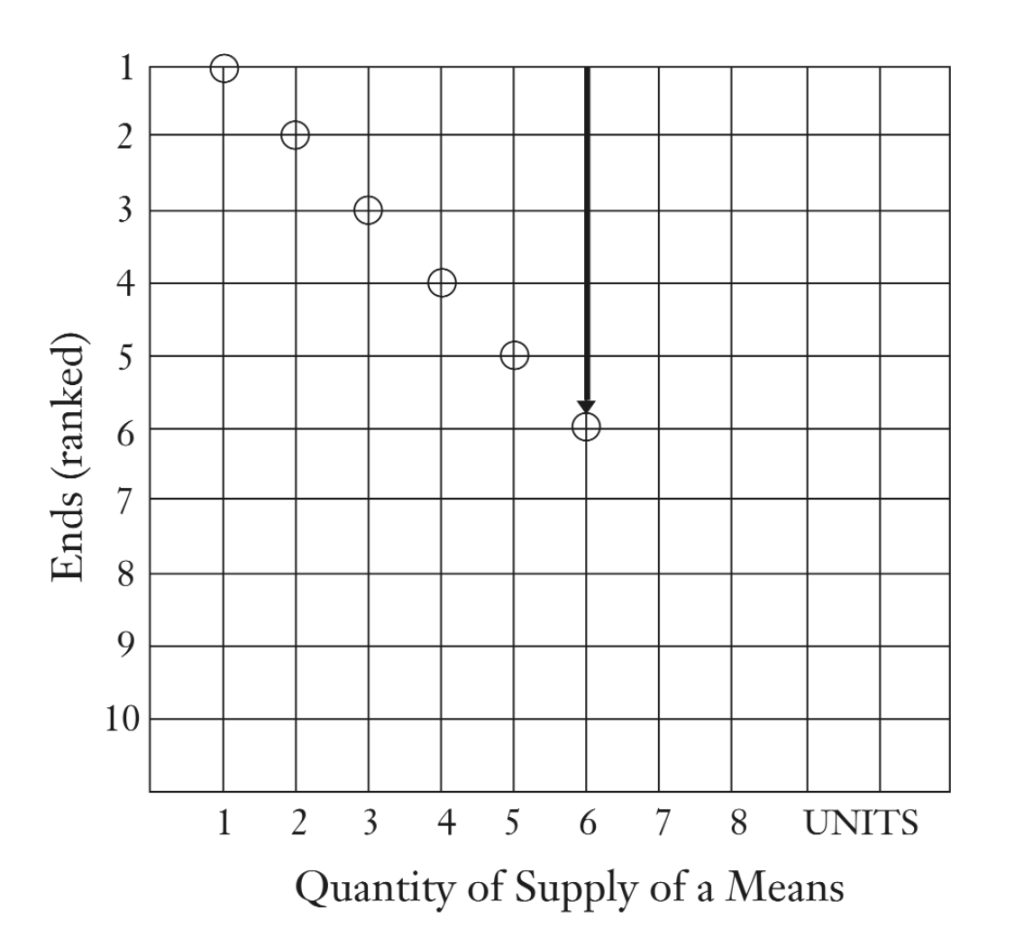

Let´s take a brief look at another example of an actor`s value scale. – Mr Smith has got ten ends he wishes to achieve, ranked on the vertical line in the graph below. His most important end is shown at the top of the vertical line (1), the lowest ranked end at the bottom (10). The horizontal axis shows the number of available means (units) to achieve his ends.

Mr Smith´s value scale

(ten ends, six means)

If Mr Smith has just got, say, six units of a means (say, money units) to satisfy his ends, then the first 6 ends can be satisfied, while the ends ranked 7–10 remain unsatisfied.

The first unit of his means goes to satisfy end 1, the second unit to serve end 2, etc. The sixth unit is used to serve end 6.

The diagram illustrates what the law of diminishing marginal utility says: (1.) The utility (value) of more units is greater than the utility of fewer units (as more units help to achieve more goals); and (2.) that the utility of each successive unit is less as the quantity of the units increases.

Now, assume Mr Smith must give up one unit of his means. With 5 units, he can only satisfy 5 of his 10 ends. Given the (in this example assumed) interchangeability of the units, he gives up satisfying the end ranked 6th, and continues to satisfy the more important ends 1–5.

The important thing is: The actor gives up the lowest-ranking want that the original stock (in this case, six units) was capable of satisfying.

This is called the marginal unit, or the unit at the margin. This least important end fulfilled by the stock is known as the satisfaction provided by the marginal unit, or the utility of the marginal unit—in short: the marginal utility. In the graph above, the marginal utility is ranked 6th among the ends.

So far we have considered consumer goods. But what about so-called producer goods – goods that are produced and then used for producing consumer goods and/or other producer goods?

Producer goods (the factors of production that cooperate in the production of consumer goods) have no immediate connection with the satisfaction of human wants. However, through the causal production process they indirectly bear on the process of want satisfaction.

The entrepreneur will attempt to employ a production good/factor at the price that will be at least less than its (discounted) marginal value product (MVP). The MVP is the monetary revenue that may be attributed, or “imputed,” to one unit of the production good.

The important point is: The value of a consumer good (from the viewpoint of consumers) is imputed to producer goods employed in its production, because the latter is a necessary, if indirect, cause of the satisfaction which is directly attributable to the quantity of consumer goods.

Suppose, for example, that a firm is combining factors in the following way:

4X + 10Y + 2Z → 100 gold oz.

Four units of X plus 10 units of Y plus two units of Z produce a product that can be sold for 100 gold ounces.

Now suppose that the entrepreneur estimates that the following would happen if one unit of X were eliminated:

3X + 10Y + 2Z → 80 gold oz.

The loss of one unit of X, other factors remaining constant, has resulted in the loss of 20 gold ounces of gross revenue.

This, then, is the MVP of the unit at this position and with this use.

We can also reverse this process. Suppose the firm is at present producing in the latter proportions and reaping 80 gold ounces. If it adds a fourth unit of X to its combination, keeping other quantities constant, it earns 20 more gold ounces. So that here as well, the MVP of this unit is 20 gold ounces.

In this example, a producer would be willing to pay up to 20 ounces of gold for one unit of X, that is the MVP of X.

Now let us turn to money and ask: What about the value of money?

Money is a good like any other. It is only “special” in the sense that it has the highest marketability/liquidity.

Being a good like any other, the value of money (from an individual´s point of view) falls under the law of diminishing marginal utility (the economic law that was outlined earlier).

With this in mind, we can understand what happens if the number of money units in the hands of an individual actor increases: The marginal utility of the money unit declines.

And what happens if there is an increase in the quantity of money in the economy as a whole? Ludwig von Mises (1881–1973) gives the answer:

“An increase in a community’s stock of money always means an increase in the amount of money held by a number of economic agents, whether these are the issuers of fiat or credit money or the producers of the substance of which commodity money is made. For these persons, the ratio between the demand for money and the stock of it is altered; they have a relative superfluity of money and a relative shortage of other economic goods. The immediate consequence of both circumstances is that the marginal utility to them of the monetary unit diminishes. This necessarily influences their behaviour in the market. They are in a stronger position as buyers. They will now express in the market their demand for the objects they desire more intensively than before; they are able to offer more money for the commodities that they wish to acquire. It will be the obvious result of this that the prices of the goods concerned will rise, and that the objective exchange-value of money will fall in comparison. But this rise of prices will by no means be restricted to the market for those goods that are desired by those who originally have the new money at their disposal. In addition, those who have brought these goods to market will have their incomes and their proportionate stocks of money increased and, in their turn, will be in a position to demand more intensively the goods they want, so that these goods will also rise in price. Thus the increase of prices continues, having a diminishing effect, until all commodities, some to a greater and some to a lesser extent, are reached by it. The increase in the quantity of money does not mean an increase of income for all individuals. On the contrary, those sections of the community that are the last to be reached by the additional quantity of money have their incomes reduced, as a consequence of the decrease in the value of money called forth by the increase in its quantity … . The reduction in the income of these classes now starts a counter-tendency, which opposes the tendency to a diminution of the value of money due to the increase of income of the other classes without being able to rob it completely of its effect.”4

By taking recourse to the law of diminishing marginal value, Mises explains that (i) an increase in the quantity of money lowers the exchange value of the money unit; that (ii) it affects different actors differently, making some richer at the expense of others; and that (iii) it causes disruptions in the economic (and financial) process (potentially causing boom and bust5).

Finally, in this context, I should be noted that money`s subjective value is conditioned by its exchange value or purchasing power: “In the case of money, subjective use-value and subjective exchange value coincide.”6 For money has not utility, or value, for the actor than that arising from the possibility of exchanging it against other vendible items.

Now let us turn to the question: What about the value of the firm, or a firm´s stock price?

As we have seen, when a good is being subjectively valued, it is ranked by someone in relation to other goods on his value scale.

However, when a good is being “evaluated” in the sense of finding out its “market value”, the evaluator estimates how much the good could be sold for in terms of money (in the future).

This sort of activity is known as appraisement, and it needs to be distinguished from subjective valuation.

If Mr X says: “I shall be able to sell this stock next week for 250 US$,” he “appraises” the stock`s purchasing power, or its money price, at 250 US$.

He does not rank the stock and US$ on his own value scale, but is appraising the money price of the stock at some point in the future.

You may ask: How does Mr X come up with his estimate of 250 US$ for the stock?

Well, he might have a “model” in mind – like, say, the discounted cash flow model (according to which a company is “worth” the present value of all its future cash flows, discounted to the present day); or he may use a concept such as multiplying a firm`s annual profit by a multiple; or he just got a gut feeling.

Appraisement (of an asset like, say, a stock, a commodity) involves individual acting, and successful appraisement requires entrepreneurial spirit and talent, acumen: Some people are good at it (in terms of grasping a stock´s future market price), while others fail in this endeavour.

That said, it does not take wonder that in the real world, there are great differences of opinion concerning the appraised value of a firm, and therefore the appraised value of each share of the firm’s stock.

If Mr X comes to the conclusion that the market price of a stock should be, say, 250 US$ (his appraised price for the stock), while the stock currently trades at, say, 500 US$, he might wish to sell the stock (thereby preventing him from a capital loss).

We get right back into the issue of subjective value, however, as soon as Mr X sells his stock in the market for, say, 250 US$. For this shows that he values the stock on his personal value scale less highly than the number of US$ he receives in exchange for it. (Likewise, the buyer values the stock more highly than the 250 US$ he surrenders.)

Let us conclude this little article on value with an instructive quote from Carl Menger:

“Value is thus nothing inherent in goods, no property of them, nor an independent thing existing by itself. It is a judgment economizing men make about the importance of the goods at their disposal for the maintenance of their lives and well-being. Hence value does not exist outside the consciousness of men. It is, therefore, also quite erroneous to call a good that has value to economizing individuals a “value,” or for economists to speak of “values” as of independent real things, and to objectify value in this way. For the entities that exist objectively are always only particular things or quantities of things, and their value is something fundamentally different from the things themselves; it is a judgment made by economizing individuals about the importance their command of the things has for the maintenance of their lives and well-being. Objectification of the value of goods, which is entirely subjective in nature, has nevertheless contributed very greatly to confusion about the basic principles of our science.”7

- Menger (1871), Principles of Economics, p. 115. – In Menger’s view, value is, so to speak, a bilateral relationship between the individual and an economic good. In contrast, to Mises, as Hülsmann (2003, pp. xxxvi–xxxvii) points out, value is actually a trilateral relationship involving the actor and two economic goods: The value of a good is determined by the actor´s preference in that he values one good to (at least) the other good subject to the same choice; in this context, just think of a situation in which an actor ponders over spending his 1 dollar bill (first good) on an apple (second good) or not.

- See Hoppe (1999), Murray N. Rothbard: Economics, Science, And Liberty, pp. 227–8.

- See Rothbard (2009), Man, Economy, and State, pp. 21–33, esp. p. 25 ff.

- Mises (1953), The Theory of Credit and Money, p. 139–140.

- This would be especially the case if the increase in the quantity of money is via credit markets.

- Mises (1953), The Theory of Credit and Money, p. 97.

- Menger (2007), Principles of Economics, pp. 120–1.

***