By Brendan Brown

The severe losses for the center-right parties in the mid-summer French and British general elections, (i.e., Macron’s center-right coalition partners and Britain’s Tories) together with a shift in the US toward MAGA within the Republican Party, pose a severe and possibly existential challenge to the ideal of sound money. This is despite surveys revealing strong and broad popular anger about the cumulative loss of purchasing power of their money during the pandemic and its aftermath.

Moreover, the hypothesis that the ideal of sound money gets a political fillip during and following a serious episode of inflation, is mythological rather than based on research from the laboratory of monetary history. The expectation that there will be responsive changes in monetary regime triggered by popular dissatisfaction is flawed. It is true that sometimes a bad inflation episode gives way to a run of good luck during which recorded inflation is low or even zero for many years. When this happens, however, the monetary regime remains fundamentally unsound.

Illustrations include first the US inflation of World War I (spanning the years of neutrality followed by US participation) and its immediate aftermath. The cumulative surge in prices was followed by largely stable prices through the 1920s (after a brief sharp fall of prices in the Great Recession of 1920-1) This stability masked, however, serious monetary inflation camouflaged by soaring productivity (during the second industrial revolution)and a collapse in commodity prices.

Then the high inflation of World War II and the further bouts of inflation through 1946-7 and 1950-52 (during the Korean War) were followed by stable prices through the mid-1950s and low inflation into the early 1960s. Fundamentally, though, monetary conditions remained inflationary and the monetary regime in place was defective.

Unsoundness showed up in two main respects. First there was the asset inflation, including the “Eisenhower Boom”, albeit periodically reined back by the Martin Fed “taking away the punchbowl” which should not have been there in the first place. Second, there was the absence of some sustained falls in prices which would have occurred under sound money in the aftermath of the Korean War and later in the economic miracles (featuring extraordinary growth in productivity) across much of Europe, Japan and indeed the US.

Disappointment about the failure of a sound money to occur in the 1950s has some resemblances to the present situation. The Eisenhower Campaign in 1952 made much of the Truman Democrats’ inflationary failures. But there was no new regime on offer – just jumbled manifesto sentences about how in the long run a growing return to gold convertibility of money internationally would contain inflation danger. There was no mention of restored gold convertibility in the US.

The focus of the campaign was policy failures leading in the start and conduct of the Korean War and about the perils of communism on the home front. Recent research does nonetheless support the hypothesis that anger about losses suffered on war bonds due to the inflations of 1946-7 and 1950-2 did fuel support for the Republicans and their anti- inflation messaging.

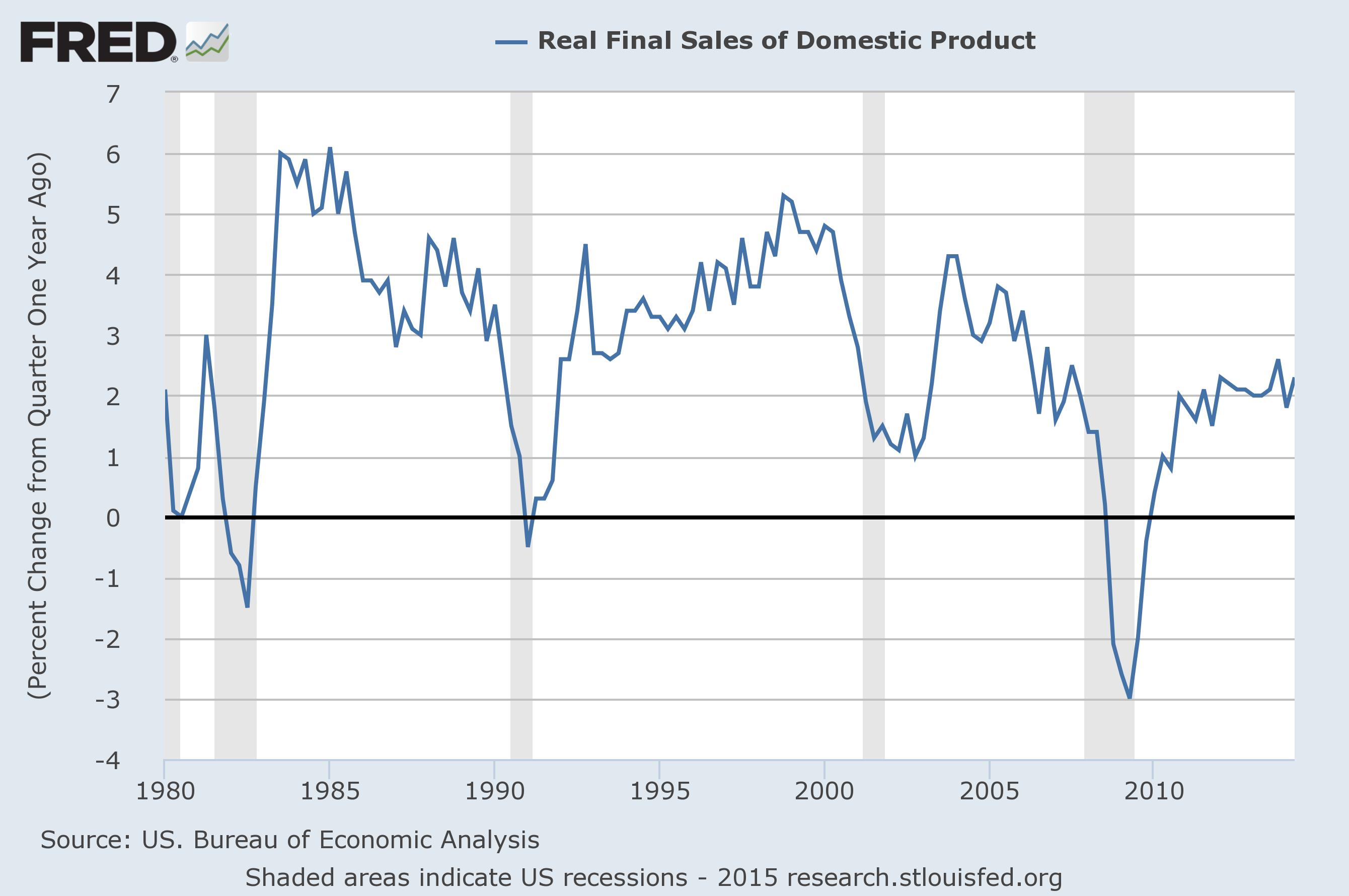

The sequel of a good luck period with respect to consumer price inflation remains a possibility for the aftermath of the Great Pandemic Inflation and the Post-Pandemic Inflation. The< prospect of a sound money regime emerging, however, is, for now, remote. Popular anger at sustained price rises and losses in real terms on money and bond holdings is offset for many individuals by apparent gains from asset inflation. This is different from the situation in 1952. And, there is a new crucial factor particular to this present inflation cycle: the Centre-Right of the political arena, the traditional conduit for pressure from sound money, is imploding.

The sound money idealists in principle could try to establish a home in the ascendant nationalist conservative forces on the Right. Without naming names, there are some isolated examples of this. But even if they offer to consummate “unholy alliances” regarding support for immigration and protectionism, there is no record among modern nationalist or populist conservatives of achieving success on sound money propositions.

It is apparent that the nationalist Right sees no election opportunity in substantial alliance-making with the hard money folk. Yes, in the US, the Trump Campaign and congressional downstream Republicans are taking aim at the Biden inflation, but there is no prominent credible or plausible hard money advocacy within the core messages. Yes, cutting some budget outlays figures there, but with no overall sea-change in the rotten public finances. In any case, monetary reform is fundamentally distinct from fiscal policy reform, albeit with connexions between the two.

Of course, the political arena is now highly volatile and unpredictable. There is also much blurring and fog around the main themes. For example, narratives popularized by the populist Right and the progressive Left about how globalism has failed do not make distinctions between key factors. For example, critics of globalism generally don’t distinguish between the huge policy mistakes regarding China’s admission to the “free trade” system, and the case for or against free trade in general. And, the anti-immigration clamor has much to do with specific errors and failures in actual legislation or implementation.

This clamor can decrease in the long term. A new status quo could evolve with respect to China. The malinvestment in excess international supply chains during the great asset inflation will fade into various forms of economic obsolescence. New legislation on immigration, and its implementation, could gain acceptance across most of the political spectrum. That may well happen if present long-run demographic projections – with respect to ageing and decreases in populations – turn out to be anything like correct.

In sum, the present factors which have caused the centre-Right to implode may evolve in ways where this grouping can re-invent itself and include an important component based around sound money. Particularly helpful here would be a working-together here in the political arena of sound money forces and the forces which would tackle the monopolistic “capitalism” of our “too-big-to-fail” bailout system. Unsound money and the growth of this inflation-fueled, bailed-out monopoly capital helps to explain the overall low growth rates of living standards in the advanced economies during recent decades. Fundamental to sound money is a new vigor of competition not just in the obvious ground of big tech but more generally and specifically in the banking sector.

We should not rule out that politics could evolve in a way where sound money idealism re-emerges in prominence in a strengthened right wing of the political left – such as occurred in the heyday of German monetarism through the late 1960s and 1970s. The question here would be the feasibility of unholy alliances on a wide range of social economic issues, and whether there could be a re-kindling of enthusiasm on the Left about how sound money, free trade, and anti-trust policies could raise living standards for the middle class in a meaningful way.

The US has its own history of monetary reform emerging from the centre Left, including the nomination of Paul Volcker as Fed Chair by President Carter (who had campaigned in 1976 against Republican inflationary policies). But this had a much more ambiguous track record than the German precedent. There was a lack of any serious commitment beyond a brief period of super-high policy interest rates and a termination in a few years with the dollar devaluation policies pursued at Plaza (1985) and beyond. (To be fair, a partial turn toward relatively sound money did continue under the subsequent Republican Administration, but with Volcker still in place.)

Yes, there are grounds for despair about the future of the sound money ideal. And, there is much about the present monetary environment which fits the description of a dark age. Under such circumstances the cause of sound money, if not simply a dream, would have to include a dimension of realpolitik.

Source: https://mises.org/power-market/high-inflation-followed-demands-sound-money-usually-not

Humans cannot be trusted with money supply.

It is that simple.

If you have the means to “print” money that others will exchange their labour and assets for, you will do it. And governments are the worst of all at it. Right or Left does not matter there.

Separation of Money and State is the only way forward, and it might be underway.

imagine a world in which governments around the world have very limited room for debasing the money that people actually hold, even if they can debase the money people actually exchange.

Gresham’s law is usually overlooked, because it is subtle, you see the bad money being exchanged, but the good money being hoarded is less obvious.