“There is always one, more prosaic, test of a nation’s position: Are people trying to get into it; or to get out of it? I think we know the answer to that in America’s case; the United States offers more freedom and opportunity than any other in history.” — Prime Minister Tony Blair

Most constitutional scholars don’t talk about it. My uncle, Cleon Skousen, who gave week-long seminars on the Constitution, barely mentioned it. In his attack on the 1787 Constitutional Convention, the economic historian Murray Rothbard made no reference to it.

And yet, this little-known section found in Article I of the Constitution could be the key to American exceptionalism. Indeed, it explains why the United States became the economic powerhouse of the world by the late 19th century.

I spoke on this topic last week at the J. Reuben Clark Law Society in Orange, California. The title of my talk was: “The United States Common Market and the Constitution: How a Gigantic Free-Trade Zone Made America the World’s #1 Economic Superpower.”

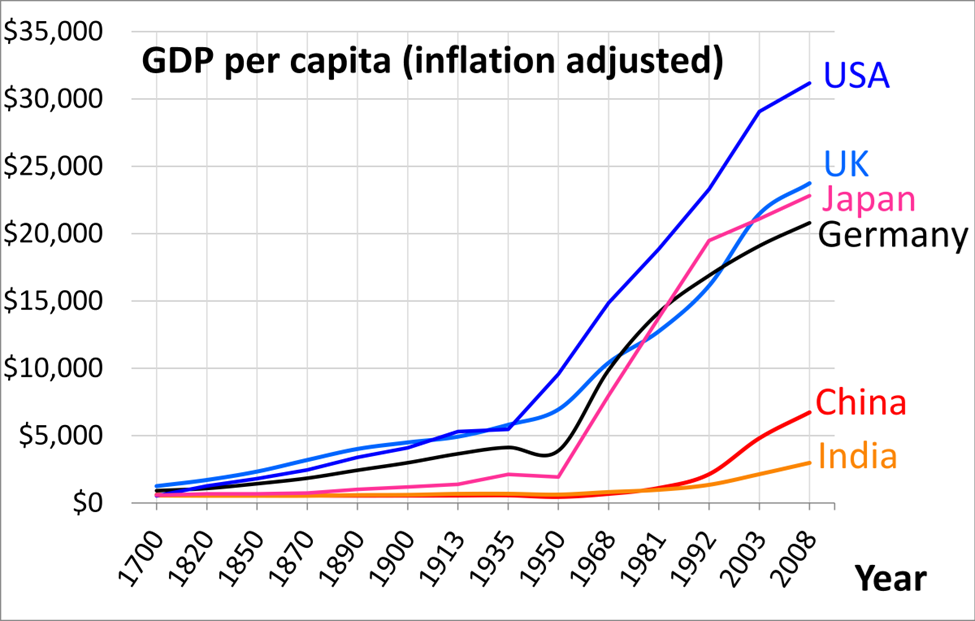

This chart shows how America gradually dominated the world economy:

Was it the Commerce Clause?

One of the lawyers there suggested it was the Commerce Clause in Article I, Section VIII that is the secret to America’s success. The Commerce Clause gives Congress the power “to regulate Commerce with foreign nations, and among the several states, and with the Indian Tribes.”

But Section VIII of Article I of the Constitution tells Congress what it can do, and that is interfere with commerce. Unfortunately, the Commerce Clause has been a major source of ever-increasing authority by Washington bureaucrats, which alone would not necessarily make America great.

As I told the audience, you can drive a truck through Section VIII of the Constitution, which gives the Federal government virtually unlimited powers to tax, regulate, borrow money, print money and declare war. It is Section VIII that has allowed government to become bloated and almost out of control. This is one area where I wish limits were placed on Congress and the chief executive.

It was ‘The Dormant Commerce Clause’!

And that brings me to another section: Sections IX and X of Article I of the Constitution, known as the “dormant” Commerce Clause. This is the part of the Constitution that limits the role of the government, the powers denied to Congress and, in this case, the powers denied to the 50 states of the union.

Section IX states clearly, “No Tax or Duty shall be laid on Articles exported from any State.”

It adds, “No Preference shall be given by any Regulation of Commerce or Revenue to the Ports of one State over those of another: nor shall Vessels bound to, or from, one State, be obliged to enter, clear, or pay Duties in another.”

Then in Section X, the Constitution states, “No State shall, without the Consent of the Congress, lay any Imposts or Duties on Imports or Exports, except what may be absolutely necessary for executing its inspection Laws: and the net Produce of all Duties and Imposts, laid by any State on Imports or Exports, shall be for the Use of the Treasury of the United States; and all such Laws shall be subject to the Revision and Control of the Congress.”

John Marshall, Chief Justice from 1801 to 1835, made it clear what this section meant. In 1824, in the case Gibbons v. Ogden, he maintained that the “sole question” before the Supreme Court was: “Can a State regulate commerce… among the States, while Congress is regulating it?” He answered in the negative. No, it can’t.

A Gigantic Free-Trade Zone in America

In essence, Sections IX and X created a gigantic free-trade “common market” among the 50 states, from sea to shining sea. No state can stop you at the state border, impose tariffs and quotas on goods being brought into the state (except to check for diseases) or leaving the state. You don’t need a work permit when you move to a new state (except in the case of licensing), and you don’t need permission to invest in one state or another.

During the past 250 years, no other country was able to create such a massive free-trade zone like the United States, taking full advantage of our spectacular natural resources, rivers, mountains and a “melting pot” of immigrants.

America was one of the first countries to adopt Adam Smith’s free-trade model. Benjamin Franklin, who was friends with Adam Smith, supported Smith’s criticism of protectionist measures. “No country was ever ruined by trade,” Franklin declared.

Europe has tried to imitate U.S. policy with its “United States of Europe,” the European Union, which now consists of 27 countries that have a common market in goods, capital, currency (the euro) and employment (no work permits).

Americans Endorse Domestic Free Trade

Constitutional lawyer Norman Williams concludes, “The United States Constitution commits the nation to a liberal, free-trade regime among the states. That commitment is embodied in several constitutional provisions that limit the authority of the states to restrict interstate trade or commerce, most notably the ‘dormant Commerce Clause.’ As the Supreme Court has observed, these provisions effectively create a common market trading system for the nation.”

He adds, “Beginning as early as the middle of the nineteenth century, the Court actively rooted out and invalidated state laws that sought to discourage the sale of out-of-state goods or services so as to favor local economic interests. Since then, numerous ‘discriminatory’ measures have been struck down by the Court. Indeed, as others have noted, this antipathy to local protectionism has been a hallmark of the Court’s Commerce Clause jurisprudence.”

The Constitution Saved the Day during the 2020 Lockdown

Sections IX and X saved us during the 2020 pandemic/lockdown. Notice that the borders between the United States and Canada/Mexico, as well as other countries, were closed. Most international flights ended. But not domestic flights between the states. You could still drive and fly within the 50 states. A few states tried to impose travel restrictions, but they didn’t last. In almost every case, you were never stopped by the state police when driving from California to Nevada, or from Georgia to Florida. We can thank the Constitution for that.

Four Other Factors that Made America #1

In my talk last week, I mentioned four other factors that contributed to America’s dominance into the 20th and 21st centuries, in addition to the “dormant commerce clause”:

- Constitutional support for patents and copyrights

- A strong dollar. The dollar has become the world’s currency

- Free trade (declining tariffs)

- Open immigration (until recently)

Put together, the United States has become the world’s #1 superpower. We can only hope it remains so.

It is a shame that Skousen ruins his analysis with this comment:

“In my talk last week, I mentioned four other factors that contributed to America’s dominance into the 20th and 21st centuries, in addition to the “dormant commerce clause”:

Constitutional support for patents and copyrights”

Skousen is completely wrong and illiberal on IP, and unfortunately this mistake contaminates his analysis. It is odd and gratuitous–not to mention incorrect–to mention US IP law in a discussion of free trade. It is ironic and even perverse, since patents are contrary to free trade and property rights and free markets, as the free market economists of the 1800s recognized. In fact, as I explain in The Anti-IP Reader: Free Market Critiques of Intellectual Property https://www.stephankinsella.com/ip-reader/:

“Free market economists began to object to the patent system in the mid-1800s, leading some countries to repeal or delay adopting patent laws. The primary criticism was that protectionist patent grants are incompatible with free trade. However, the “Long Depression” starting in 1873 turned public opinion against free trade, leading the anti-patent movement to collapse and for modern patent systems to eventually become dominant world-wide.”

Patent law distorts and impedes innovation and slows down innovation and reduces human wealth. See my book You Can’t Own Ideas: Essays on Intellectual Property https://www.stephankinsella.com/own-ideas/ and Legal Foundations of a Free Society https://www.stephankinsella.com/lffs/, Part IV. Many others recognize this as well, including commentators from the Cobden Center. Toby Baxendale has pointed this out, for example, in this post https://www.cobdencentre.org/2010/09/goods-scarce-and-nonscarce/ and the IP problem has been recognized by others at the Cobden Centre, e.g, https://www.cobdencentre.org/2022/01/intellectual-property-fire-and-other-dangerous-things/ and Andy Duncan. https://www.cobdencentre.org/2010/11/stephan-kinsella-intellectual-property-in-history/

It is shame Skousen is unaware of this and is confused on IP and taints his analysis of free trade by perversely supporting state-granted monopoly privileges that distort and impede innovation. In this he reminds of pro-patent Cato Institute scholars who, faced with the choice of either supporting patent law and the monopoly prices and restrictions on competition that it gives rise to, or free trade—sadly and embarrassingly chose to abandon free trade for the sake of supporting local patent-cased monopoly prices. On this, see https://www.stephankinsella.com/2009/12/drug-reimportation/

Skousen is wrong in thinking patent law is just, or that it is necessary for, or gives rise to, innovation. He is wrong in thinking that patent and other IP rights are property rights, he is wrong in thinking they are compatible with free markets and freedom and property rights. There are many old-school libertarians who are confused and wrong about IP. They should have the decency to bow out of these matters since they obviously do not understand how to mount a principled case for property rights; if they did, they would not support socialistic and statist schemes like the patent system that grants anti-competitive monopoly privileges. If Skousen is so bad on such a fundamental issue, it makes one wonder what else he gets wrong in his economic and political analyses.