In the past year we have witnessed the growing influence and clout of the Occupy Wall Street movement in the States, the St. Paul’s protestors, or any other of the numerous regional protests spreading around the developed world. Although at times difficult to pinpoint exactly what has gotten these groups so upset – whether lack of jobs, austerity cuts, or the like – there does appear to be one common concern. The growing divide between the “rich” and the “poor” seems to be increasing, and this is causing alarm.

In most cases of economic advance we have seen a growing divide between the haves and the have-nots. This makes sense for many reasons. In a market economy one ends up having much by providing others with much. It is only by ensuring that others’ needs are best met that the businessman can attract clients. On another level, we should not forget that just because there is a growing divide between two tiers in society, that does not imply that both are not better off as a result. We can think back to Margaret Thatcher’s final speech in parliament when the Right Honourable Gentleman opposite chastised her government for just such a growing divide. Thatcher’s response was fitting as an end to her terms as Prime Minister, but also to the Britons whose lives were made better under it – even though several British citizens had gotten wealthy (even fabulously so) under her tenure, the average Briton had also seen their quality of life improve immensely. Indeed, it was probably those at the lowest echelon of society – the destitute with no jobs in the 1970s – that benefited the most as their lives gained new meaning in the booming 1980s.

Today’s divide is different, however. The rich are getting richer and there is no discernible improvement in the life of the average Briton. Indeed, inflation adjusted salaries are lower than they have been in a decade. Instead of the rich spending their largess on investment that improves the lives of the rest, they are spending it on what many see as superfluous luxuries.

In 2010, Sotheby’s London set a new auction record with the £65m sale of Giacometti’s “L’Homme qui Marche 1”. While many housing markets remain in tatters, mega-mansions are doing fine. During the peak of the boom in 2007, the highest price paid for a home outside of London was outside of Henley-on-Thames. The selling price was £40m. Last autumn the same house sold for £140m. The Knight Frank Wealth Report reports that 25 percent more high net worth individuals are expressing an interest in fine art in 2011 than the previous year.

These ostentatious displays of wealth are sure to evoke feelings of insecurity and ire from the have-nots. They are purchases that only a small fraction of the population can afford, and benefit from.

The difference in the wealth divide that exists today compared to its 1980s has a simple explanation. They are caused by different conditions.

Take a sustainable economic advancement. The business setting improves, taxes are lowered and regulations done away with (or made more sensible) and conditions of low price inflation allow for easy monetary calculation. Businessmen follow their natural urge to serve wants better than others in hopes of earning a monetary gain. If they do this well and customers demand their products, these businessmen hire additional workers. Everyone wins – the business leaders get remunerated for their foresight and hard work with wealth, workers get jobs, and customers gain access to new goods. Each worker sees his wealth increase due to a new or better job. The businessman gains even more – he earns additional money from each and every one of these additional workers he hires (or else he would not have hired them in the first place). A wealth divide emerges, but all involved are better off than they otherwise would be.

That story more or less explains the growing wealth divide that defined Britain’s 1980s.

Today’s wealth divide is different. Business conditions are not improving. Taxes are not being lowered, a condition that would incentivize more entrepreneurs to start enterprises. Regulations are not easing to remove barriers to entry for smaller firms – those typically lacking the legal budgets to navigate such difficult waters. Price inflation is not exactly low, and is also highly uncertain. None of the criteria for a booming economy, one capable of causing a beneficial wealth divide, are apparent. Yet a growing wealth divide we have.

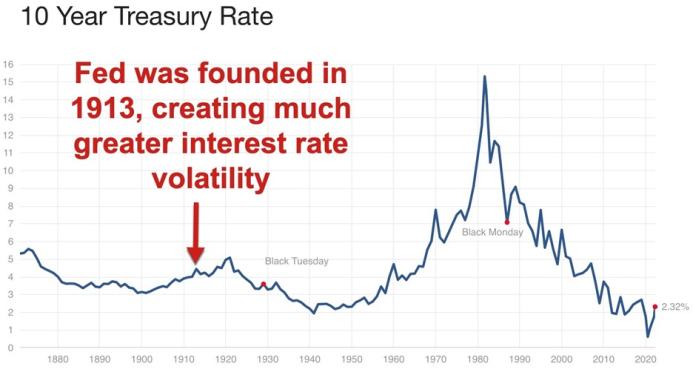

One explanation is the final criteria above – the lack of low and stable price inflation. When new money enters the economy, it does not affect all participants equally. It enters at a specific point where someone spends it. At that moment, the constellation of prices reflects an old quantity of money and spending patterns. Once this new money enters the economy, price pressure increases. The first person to spend this money benefits as they spend money which then causes prices to adjust – they can take advantage of the situation by being part of the cause of the price increase, instead of an innocent bystander.

Price inflation is not something that drives business growth. It aids some (those who first receive the money), but it complicates life for the rest of us. Each year that passes we see prices increase. They do not all do so evenly. We need to decide how best to allocate our money among the new array of prices. Those who first spend any new money are not encumbered in the same way – they are the ones that make prices increase.

Since this crisis has began, the Bank of England has embarked on a highly inflationary policy aimed at rescuing insolvent banks and aiding those nearly so. This policy has evidently not promoted economic growth in the economy. It has also advantaged those few that have early access to the funds created and have the liberty to spend them at the old pre-inflation prices. Investment managers, developers, bankers and the like – those closely involved in the process of injecting new money into the economy – have been spending the increased supply of pound notes on art, real estate and fine wines. While this gives an impression of wealth to some, it is all an illusion. It is a monetary manipulation enriching some at the expense of others.

For the rest of us – those feeling as though we are falling behind the Joneses – the object of our ire should not be those that are getting wealthy at our expense. I would do the same thing if I was in a position to receive new pounds that Mervyn King is gifting around. I would direct my ire at the root cause instead. The Bank of England’s inflationary policies since 2007 (and before) have created a special class within Britain. Members of this class get to use money to fund their consumption at old pre-inflation prices. For the rest of us, well, we get the feeling that we’re left behind.

I’d agree with the analysis in principle but when I’ve raised this issue the reply has been that the BoE has only been buying government bonds and so provided no benefit to finance.

Therefore I’d like to ask if you could elaborate on the precise mechanism with which new money finds its way into the finance sector (not including low interest rates and bail outs which are more obvious)

My understanding is that the central banks looking to lower the interest rate generally buy government bonds from primary dealers at a premium, this leads to excess reserves on these mega banks balance sheet which increases the amount that can be lent out by an order of reserves/reserve ratio.

For bankers this leads to larger balance sheets and larger profits.

For the wealthy that borrow big amounts (it’s not the poor borrowing this fraudulent money) it also leads to huge profits.

Note, I’m no expert, everything I mentioned comes from skimming Mises Daily articles for years.

I should probably pick up Rothbard’s “WHAT HAS GOVERNMENT DONE TO OUR MONEY?” some time to learn more.

David Hope:

it is more a question of who uses the money first. If banks receive the funding and either: a) stay afloat or b) pay out bonuses, those employees are getting the funds before the rest of us. (By definition — their spending is what gets the funds to the rest of us.) Alternatively, banks could loan that money out, in which case whoever is doing the borrowing is getting to spend the money first. The key in each case is that whoever gets the money first spends it and this causes inflation. Their expenditures are made at the old prices, and only through these expenditures do prices increase. They get relatively richer, while we get relatively poorer as the prices we pay go up.

Criteria is plural.

Thanks for your replies. Perhaps my question was not quite precise enough.

Really what I am wondering is how banks(and similar) get money first. I can see how this happens in an interest rate change and in a bailout or when they lower reseves. I wanted to know if you also think this has occurred in QE and if so how or whether you didn’t count this. It seems in QE although it benefits government debt it doesn’t directly help banking, at least in the uk version.

To begin by responding to David Hope some more…

A commercial fractional reserve bank “monetizes” assets. That is, it has loans and lenders pay it interest, so these loans are assets. It then offers bank account balances to it’s customers. If you have a bank account your lending to the bank, there is no “money in the bank” that you own. Lots of Austrian Economists are critical of this process, I agree with some of their criticisms and disagree with others.

Amongst the assets banks own are government bonds and central bank reserves. Central bank reserves are what has taken the place of gold in the banking system today. Reserves are what act as money between banks. In many systems a commercial bank must hold a particular amount of them, by law. In Britain holding them is optional, but for various reasons that doesn’t change things much in practice. Now, sometimes a central bank does monetary “easing”, both quantative easing and normal interest rate cutting work by the same process, they are really no different. That means the central bank buys bonds and pays for them with reserves. Those reserves allow the commercial bank to create greater bank balances. The central bank’s action of buying bonds drives up the price of those bonds compared to what they would have been. So, the commercial bank obtains reserves that allow it to create money at a knock-down price.

There are other processes that enrich commercial banks, notably the interest rate carry trade where they borrow from the central bank at a low interest rate and buy other assets that have higher interest rates.

That credit-money expansion leads to an ARTIFICIAL increase in inequality should be well known.

After all Richard Cantillion (John Law’s partner in “legal” crime) outlined how this process works – way back in the 1700s.

The fact that people still do not understand that is credit-money expansion (even after the boom-bust has run its course) that is ARTIFICIALLY increasing inequality, is depressing.