The evidence of a major breakdown in global economic and monetary cooperation continues to mount. Just yesterday, the G7 released a statement regarding foreign exchange policies, only to be followed by a corrective statement that the market reaction was undesirable. This indicates escalating tensions within the G7. But if the G7 cannot cooperate, how on earth will the G20 do so? Or other countries? We are witnessing in real time a descent into economic nationalism that increasingly resembles the 1920s and 1930s. Then, as now, such nationalism resulted in major economic damage, with every single currency devaluing sharply versus gold, and with every single stock market underperforming gold. History is rhyming, loud and clear.

WHAT WE HAVE HERE IS A FAILURE TO COMMUNICATE

On several occasions I have predicted a breakdown in international economic and monetary cooperation, most extensively in my book, The Golden Revolution (link here), but also in the pages of this report and in several TV interviews, including an appearance on the Keiser Report just last week (watch here). But I must admit even I was taken by surprise by the astonishing behaviour of G7 officials yesterday.

To much anticipation, the G7 countries (US, Canada, UK, Germany, France, Italy and Japan) released an official communique early in the morning European time regarding their foreign exchange policies. Among other things the statement said that the G7 “will not target exchange rates.”[1]

So far, so clear. The entire statement was also entirely consistent with the previous G7 communique from September 2011, which read in part that “We reaffirmed…our support for market-determined exchange rates.”

Given this degree of consistency between the two statements and lack of any specific mention of the yen, the foreign exchange markets determined that the G7 was giving tacit approval for Japan to continue to weaken the yen, which has declined by 10-15% versus all major global currencies in the past few months. The yen declined by another 1% versus the dollar and euro in the hours following the release of the statement.

Apparently, however, this was not the reaction all G7 members in fact desired. As the yen continued its decline, an unidentified G7 official came out with a highly unusual (and possibly unprecedented) qualifying statement, saying that:

The G7 statement signaled concern about excess moves in the yen. The G7 is concerned about unilateral guidance on the yen. Japan will be in the spotlight at the G20 in Moscow this weekend.[2]

Whoa! Well G7 members are either concerned specifically about the yen or they are not. So it would seem that certain members of the G7 desired to include a specific comment on the yen but that certain other members vetoed this. Now who might that have been? Japan itself comes to mind and, given that Japan has been the biggest single purchaser of US Treasury securities over the past year, it seems reasonable to assume that the US supported Japan with the veto. The UK and Canada have now both said they made no such comment.

Taking the other side would logically have been the euro-area countries. While Germany is widely known to compete with Japan in a broad range of global export markets, there is also a degree of such competition with France and Italy. Indeed, on a per-capita basis, northern Italy is as large a world exporter as Germany, producing a huge range of manufactured goods, including precision machinery vital to many global industries. There are also such pockets in France, including around Paris, Lyon, Lille and Strasbourg. (I am excluding agricultural products here, although both Italy and France are wine and cheese export powerhouses.)

Yesterday’s unusual G7 drama thus appears to confirm what I claimed in my last report, COUNTDOWN TO THE COLLAPSE (link here), that Japan broke a temporary ‘cease-fire’ in the ‘currency wars’ with the sharp weakening of the yen in Q4 last year. In that report I also indicated that the UK was likely the next country to join hostilities.

Sure enough, in a press conference earlier today, Bank of England Governor Mervyn King said that “it’s very important to allow exchange rates to move,” and that “when countries take measures to use monetary stimulus to support growth in their economy, then there will be exchange rate consequences, and they should be allowed to flow through.”[3] These bold comments could be interpreted as embracing rather than eschewing the escalating currency wars. They also indicate that the UK desires a weaker sterling.

If even the relatively closely-knit G7 can’t cooperate in foreign exchange matters, why should we be confident that the G20 can? Well, we shouldn’t be. Quite the opposite.

THE G20 COUNTRIES INCLUDE THE BRICS

The G20 is arguably the most important forum when it comes to maintaining international economic cooperation, or potentially revealing the lack thereof. I also mentioned in my last report that a key event to watch will be the upcoming BRIC summit held on March 26-27 in Durban, South Africa. Now as with all such international diplomatic gatherings, discussions and negotiations around key topics and issues begin many weeks or even months in advance. By the time the G20 meet in Moscow this weekend, you can be confident that the official BRIC position on foreign exchange matters is already under discussion.

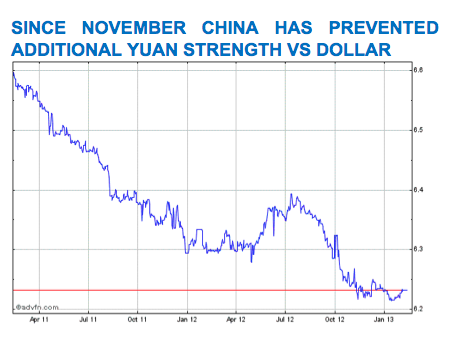

It is therefore possible that, in one or more statements by BRIC member countries at the G20, we receive a hint or two as to the evolving BRIC position. But what is it likely to be? How do the BRICs feel about the weaker yen, for example? About the fact that the South Korean won and Taiwan dollar have recently weakened and, just this week, have been joined by the Malaysian ringitt? China, for one, finds itself suddenly surrounded by sharply weaker currencies. China is also embroiled in some escalating territorial disputes with Japan and other neighbours regarding sovereignty over the South China Sea. (Note the name!) In this context, should we be surprised that China appears to have ceased allowing the yuan to rise versus the dollar of late?

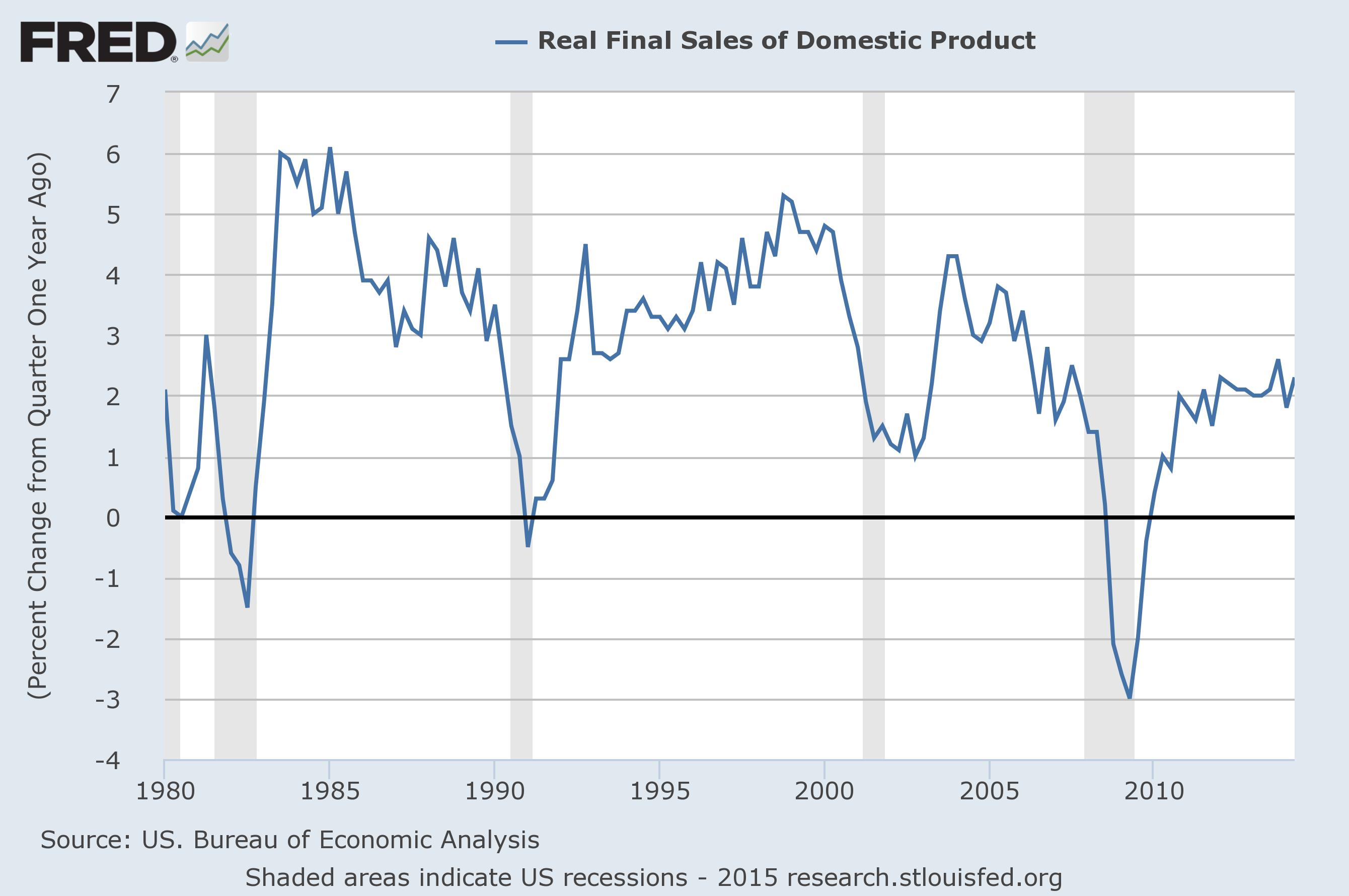

If China ceases to allow the yuan to rise, what are the chances that the other BRICs fall in line with China in the ‘currency wars’ and do the same? And if so, how is the US likely to respond? With the labour market still very weak and yet president Obama is now pushing for a rise in the minimum wage to $9/hr, is the US going to tolerate a strong dollar? The combination of higher payroll and ‘Obamacare’ taxes, a higher minimum wage and a stronger dollar would go a long way toward reversing the modest decline in the unemployment rate over the past year.

The euro-area may have even more immediate issues with the strong euro. With Greece, Spain and Portugal still mired in a deep recession, Italy teetering on the edge and France and Germany now entering at a minimum a mild recession and possibly something worse, further euro strength will be considered unwelcome.

(The German Bundesbank is an important exception here. President Weidmann said earlier this week that, “If more and more countries try to depress their currency, it will end in a depreciation competition, which will only produce losers.”[4] He also specifically criticised politicians for weighing in on currency policy, saying that “politicians should hold on to the established division of labour.”)

Now the issue of whether euro-area politicians or the ECB should be in charge of currency policy has long been in dispute. Even before the euro came into existence it was hotly contested. As it happens, the ECB has intervened in the foreign exchange markets before, back in 2000, but to strengthen the euro. The ECB has never intervened to weaken it.

This unwillingness to intervene to weaken the euro is understandable given that, since the introduction of the euro in 1999, the rate of euro-area CPI has only once strayed materially below the ECB’s 2% reference level for any period of time.[5] It would seem at odds with the ECBs mandate to maintain price stability were the ECB to intervene to weaken the euro unless the rate of CPI fell well below 2% and policy rates were already very low, implying a limited ability to prevent a further decline. As the chart of euro-area CPI below shows, there has been only one such period and, it so happens, this was primarily a base effect resulting from a previous spike. At present, the rate is 2.2%.

THE LOOMING DANGERS AHEAD

So where does this leave us? We have ample evidence that what is happening is not just a failure to communicate but a failure to cooperate. What are the implications for the financial markets?

First, foreign exchange markets are likely to become unusually volatile. This may present a headache for policymakers but when markets sense that major policy disputes are escalating they begin to force the issue by building positions.

Second, if FX volatility becomes severe enough policymakers may resort to extreme actions that spill over into other markets. For example, following a huge surge in the Swiss franc on safe-haven buying in 2011, the Swiss National Bank (SNB) chose to put in a floor of 1.20 on the EUR/CHF exchange rate, committing to ‘unlimited’ purchases of euro assets if so needed. This has resulted in an explosion of the SNB balance sheet, something that could become hugely inflationary under certain circumstances.

More dramatic would be for countries to raise trade barriers in an effort to protect domestic industries and jobs. For all the talk of ‘free-trade’ in the world, the reality is far different. A great many industries and products are subject to various kinds of frequently minor trade barriers, some of which are quite well hidden to those not involved in a particular industry or product. A political response to currency devaluations by competitors could well be to increase existing barriers or erect entirely new ones.

As I have written before, trade barriers can be hugely damaging to corporate profitability. Imagine if all of a sudden euro-area countries or US states sought to protect domestic firms and jobs by charging a 10% tariff on any goods crossing the border. With few exceptions, corporate profit expectations would collapse and the stock markets would immediately follow suit. Now extrapolate this to the global level and imagine what a trade war would do to the multinational companies that comprise the vast bulk of major world stock market capitalisation. It would make the crash of 2008 seem tame by comparison.

Third, countries might enact capital controls to stabilise their exchange rates but at the expense of preventing capital from moving efficiently across borders. Capital controls are to capital flows what trade barriers are to exports and imports and would also crush corporate profitability. Imagine trying to raise capital, rollover debt, or redeem multinational corporate debt or shares in a world of capital controls. Global financial markets in general would largely seize up. Risk premia would soar. Valuations would collapse.

Were the US itself to take the lead in any one of these extreme actions, the dollar would from that day forward cease to enjoy its long-held dominant reserve currency status and the comparatively low borrowing costs this confers. Given the huge, escalating federal, state and municipal debts, even small increases in debt servicing costs could spiral into a public debt crisis. The Fed would no doubt come under pressure to buy the bonds required to bring such a crisis under control but with global savers less able to absorb these new dollars due to capital controls, the dollars would circulate primarily domestically, leading to a potentially huge surge in price inflation.

COMMODITIES PROVIDE CHEAP INSURANCE

The colossal global debt problem, associated currency wars, looming trade wars and possible capital controls collectively threaten the real value of financial assets generally through some combination of devaluation, default and inflation. In this unusual and unfortunate situation, commodities provide a form of insurance. They cannot be ‘printed’ or otherwise arbitrarily devalued. They cannot default. They will always find some demand. Indeed, amid trade barriers and capital controls some basic commodities taken for granted today may command a large premium due to supply shocks.

As it stands now, however, commodities appear cheap relative to financial assets. Equity markets have risen strongly of late, leaving commodities the most undervalued in relative terms since 2008. Bond markets may have sold off slightly in recent weeks but in any reasonable historical comparison remain extremely expensive as a result of unprecedented and unsustainable central bank buying.

It is impossible to know just which commodities are most likely to rise in price. As a form of alternative money, gold and silver are likely to rise, in particular if there is even a partial official remonetisation of these metals as a replacement for highly unstable fiat currencies.[6] But trade barriers could restrict the flow of oil and foodstuffs, pushing up their prices to unprecedented levels.

The best action investors can take is to diversify their exposure across a broad range of essential commodities and those companies that produce them domestically and abroad. These companies are likely to retain their pricing power amid trade wars, although they may be subject to nationalisation in extreme cases.

This article was previously published in The Amphora Report, Vol 4, 12 February 2013.

[5] I use the term ‘reference’ here because the ECB lacks a formal target. The ECB’s mandate is to maintain price stability as the ECB so defines it. The ECB has long held that a rate of 2% is consistent with price stability and so 2% is a reference only, not a target.

[6] There is still much nonsense out there about how there is “too little gold or silver” in the world to serve as money. As I am fond of pointing out, the amount of gold and silver may be relatively fixed by weight and volume but not by price, which need only rise sufficiently.

“They also indicate that the UK desires a weaker sterling.”

I know you didn’t really intend that :-)