In its latest edition, in a piece entitled ‘Monetary policy: Tight, loose, irrelevant’, the ineffably dire Ekonomista considers the work of three members of the Sloan School of Management who conducted a study of the factors which – according to their rendering of the testimony of the 60-odd years of data which they analysed in their paper, “The behaviour of aggregate corporate investment” – have historically exerted the most influence on the propensity for American businesses to ‘invest’.

The article itself starts by deploying that unfailingly patronising, ‘it’s economics 101’ cliché by which we should really have long ago learned to expect some weary truism will soon be rehashed as fresh journalistic wisdom.

It may be only partly an exaggeration to say that the weekly then adopts a breathless, teen-hysterical approach to a set of results which, with all due respect to the worthies who compiled them, should have been instantly apparent to anyone devoting a moment’s thought to the issue (and if that’s too big a task for the average Ekonomista writer, perhaps they could pause to ask one of those grubby-sleeved artisans who actually RUNS a business what it is exactly that they get up to, down there at the coalface of international capitalism). Far from being a Statement of the Bleedin’ Obvious, our fearless expositors of the Fourth Estate instead seem to regard what appears to be a tediously positivist exercise in data mining as some combination of the elucidation of the nature of the genetic code and the first exposition of the uncertainty principle. This in itself is a telling indictment of the mindset at work.

For can you even imagine what it was that our trio of geniuses ‘discovered’? Only that firms tend to invest more eagerly if they are profitable and if those profits (or their prospect) are being suitably rewarded with a rising share price – i.e. if their actions are contributing to capital formation, realised or expected, and hence to the credible promise of a maintained, increased, lengthened or accelerated schedule of income flows – that latter condition being one which also means the firms concerned can issue equity on advantageous terms, where necessary, in the furtherance of their aims.

[As an aside, do you remember when we used to ISSUE equity for purposes other than as a panic measure to keep the business afloat after some megalomaniac CEO disaster of over-leverage or as part of a soak-the-patsies cash-out for the latest batch of serial shell-gamers and their start-up sponsors?]

Shock, horror! Our pioneering profs then go on to share the revelation that firms have even been known to invest WHEN INTEREST RATES ARE RISING; i.e., when the specific real rate facing each firm (rather than the fairly meaningless, economy-wide aggregate rate observable in the capital market with which it is here being conflated) is therefore NOT estimated to constitute any impediment to the future attainment (or preservation) of profit. Whatever happened to the central bank mantra of the ‘wealth effect’ and its dogma about ‘channels’ of monetary transmission? How could those boorish mechanicals in industry not know they are only to invest when their pecuniary paramounts signal they should, by lowering official interest rates or hoovering up oodles of government securities?

At this point we might stop to insist that the supercilious, wielders of the ‘Eco 101’ trope at the Ekonomista note that these firms’ own heightened appetite for a presumably finite pool of loanable funds should firmly be expected to nudge interest rates higher precisely in order to bring forth the necessary extra supply thereof, just as a similar shift in demand would do in any other well-functioning market (DOH!), so please could they take the time in future to ponder the workings of cause and effect before they dare to condescend to us.

They might also reflect upon the fact that when the banking system functions to supplement such hard-won funds with its own, purely ethereal emissions of unsaved credit – thereby keeping them too cheap for too long and so removing the intrinsically self-regulating and helpfully selective effect which their increasing scarcity would otherwise have had on proposedschemes of investment – they pervert, if not utterly vitiate, a most fundamental market process. Having a pronounced tendency to bring about a profound disco-ordination in the system to the point of precluding a holistic ordering of ends and means as well as of disrupting the timetable on which the one may be transformed into the other, we Austrians recognize this as theprimary cause of that needless and wasteful phenomenon which is the business cycle. It is therefore decidedly not a cause for perplexity that investment, quote: ‘…expands and contracts far more dramatically than the economy as a whole’ as the Ekonomista wonderingly remarks

Nigh on unbelievable as it may appear to the policy-obsessed, mainstream journos who reviewed the academics’ work, all of this further implies that the past two centuries-odd of absolutely unprecedented and near-universal material progress did NOT take place simply because the central banks and their precursors courageously and unswervingly spent the whole interval doing ‘whatever it took’ to progressively lower interest rates to (and in some cases, through) zero! Somewhere along the line, one supposes that the marvels of entrepreneurship must have intruded, as well as what Deidre McCloskey famously refers to as an upsurge in ‘bourgeois dignity’ – i.e., the ever greater social estimation which came to be accorded to such agents of wholesale advance. This truly must shake the pillars of the temple of the cult of top-down, macro-economic command of which the Ekonomista is the house journal.

Remarkably, the Ekonomista’s piece is also daringly heterodox in inferring that, given this highly singular insensitivity to market interest rates, we might therefore return more assuredly to the long-forsaken path of growth if Mario Draghi and his ilk were to treat themselves to a long, contemplative sojourn, taking the waters at one of Europe’s idyllic (German) spa townsinstead of constantly hogging the limelight by dreaming up (and occasionally implementing) ever more involved, Cunning Plans directed towards driving people to act in ways in which they would otherwise not choose to do, but in which Mario and Co. conceitedly deem that they should.

Rather, the hacks have the temerity to assert – and here, Keynes be spared! – it might do much more for the investment climate if the Big Government to which they so routinely and so obsequiously defer were to pause awhile in its unrelenting programme to destroy all private capital, to suppress all economic initiative, and to restrict the disposition of income to thecentralized mandates of its minions and not to trust them to the delocalized vagaries of the market – all crimes which it more readily may perpetrate under the camouflage provided by the central banks’ mindless and increasingly counter-productive, asset-bubble inflationism.

Having reached this pass, might we dare to push the deduction one step closer to its logical conclusion and suggest that the only reason we continue today to suffer a malaise which the self-exculpatory elite (of whom none is more representative than the staff of the Ekonomista itself) loves to refer to as ‘secular stagnation’ is because its own toxic brew of patent nostrums is making the unfortunate patient upon whom it inflicts them even more sick? That, pace Obama the Great, The One True Indispensable Chief of the NWO, the three principal threats we currently face are not Ebola, but QE-bola – a largely ineradicable pandemic of destruction far more virulent than even that dreadful fever; not the locally disruptive Islamic State but the globally detrimental Interventionist State – the perpetrator of a similarly backward and repressive ideology which the IMF imamate seeks to impose on us all; and definitely not the Kremlin’s alleged (though highly disputable) revanchism being played out on Europe’s ‘fringe’ but the Kafkaesque reality of stifling and undeniable regulationism at work throughout its length and breadth?

We might end by reminding the would-be wearer of the One Ring, as He lurks warily, watching the opinion polls from His lair in the White House, that in being so active in propagating each one of these genuinely existential threats to our common well-being, He (capitalization ironically intended) will not so much ‘help light the world’ – as He nauseatingly claimed in His purple-drenched, sophomore’s set-piece at the UN recently – as help extinguish what little light there still remains to us poor, downtrodden masses.

——————————————————————————————————-

The offending article:

Monetary policy

Tight, loose, irrelevant

Interest rates do not seem to affect investment as economists assume

IT IS Economics 101. If central bankers want to spur economic activity, they cut interest rates. If they want to dampen it, they raise them. The assumption is that, as it becomes cheaper or more expensive for businesses and households to borrow, they will adjust their spending accordingly. But for businesses in America, at least, a new study* suggests that the accepted wisdom on monetary policy is broadly (but not entirely) wrong.

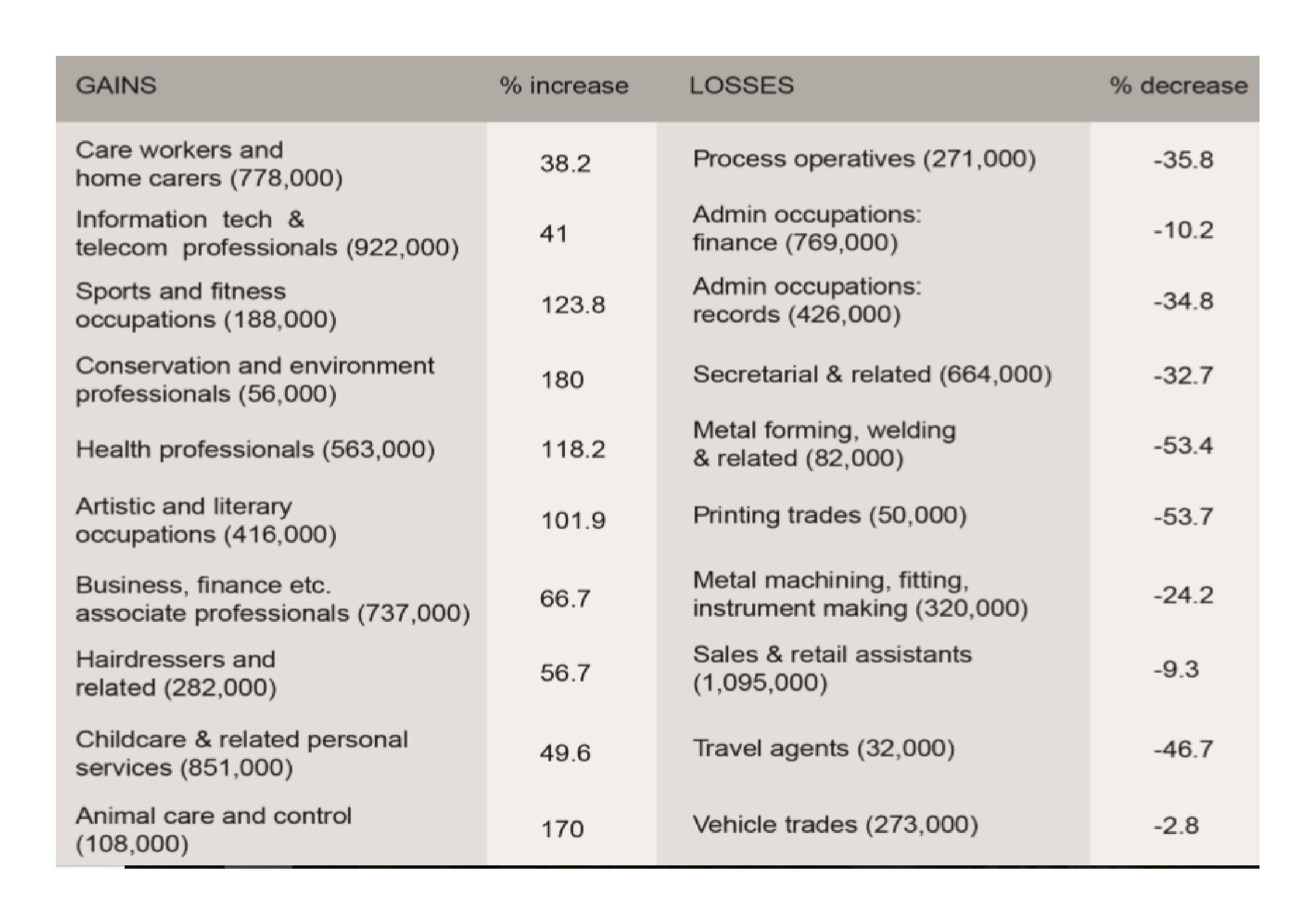

Using data stretching back to 1952, the paper concludes that market interest rates, which central banks aim to influence when they set their policy rates, play some role in how much firms invest, but not much. Other factors—most notably how profitable a firm is and how well its shares do—are far more important (see chart). A government that wants to pep up the economy, says S.P. Kothari of the Sloan School of Management, one of the authors, would have more luck with other measures, such as lower taxes or less onerous regulation.

Establishing what drives business investment is difficult, not. These shifts were particularly manic in the late 1950s (both up and down), mid-1960s (up), and 2000s (down, up, then down again). Overall, investment has been in slight decline since the early 1980s.

Having sifted through decades of data, however, the authors conclude that neither volatility in the financial markets nor credit-default swaps, a measure of corporate credit risk that tends to influence the rates firms pay, has much impact. In fact, investment often rises when interest rates go up and volatility increases.

Investment grows most quickly, though, in response to a surge in profits and drops with bad news. These ups and downs suggest shifts in investment go too far and are often ill-timed. At any rate, they do little good: big cuts can substantially boost profits, but only briefly; big increases in investment slightly decrease profits.

Companies, Mr Kothari says, tend to dwell too much on recent experience when deciding how much to invest and too little on how changing circumstances may affect future returns. This is particularly true in difficult times. Appealing opportunities may exist, and they may be all the more attractive because of low interest rates. That should matter—but the data suggest it does not.

* “The behaviour of aggregate corporate investment”, S.P. Kothari, Jonathan Lewellen, Jerold Warner