FOMC have changed their normalizing strategy several times and we now see the contours of yet another shift. The Federal Reserve was supposed to reduce its elevated balance sheet before moving interest higher as it would be impossible to increase the fed funds rate in the old fashioned way when the market was saturated with trillions of dollars in excess reserves. When it finally dawned on the FOMC that selling large quantities of TSY and MBS into the market was probably not a very bright idea, they created the O/N RRP to be able to raise rates without draining the financial system of reserves beforehand. Still, the thought of selling, or more accurately not rolling over, trillions worth of government debt, when SWF’s and foreign FX managers are desperate to raise USD is still not something the FOMC even want to contemplate.

So a case needs to be built for the FOMC to justify maintaining its bloated balance sheet indefinitely; conveniently enough ex-FOMC member Jeremy Stein with his Harvard colleagues Robin Greenwood and Samuel Hanson did just that in a paper called “The Federal Reserve’s Balance Sheet as a Financial-Stability Tool” presented at the Jackson Hole Symposium.

Their argument is simple. When the FOMC starts to raise rates, demand for positive yielding cash-like instruments will increase, thus re-enabling financial institutions to use the commercial paper market to fund themselves cheaply and enjoy a positive carry on their maturity transformation. As our chart below shows, commercial paper outstanding, with extremely short duration, grew exponentially prior to the GFC as financial institutions used the wholesale market to fund illiquid and longer dated positions.

When the crisis hit, confidence in banks evaporated and money market demand for commercial paper dried up, the cost of wholesale funding (if you could get it) became exorbitant and fire sale of illiquid assets exacerbated the GFC debacle.

To avoid excessive wholesale funding in the future, Stein et al suggest maintaining the Federal Reserve balance sheet at the current level in order to supply enough safe, liquid short term money-like assets for money market funds to invest in. Instead of scaling down the O/N RRP facility, Stein et al would rather expand it both scope and attractiveness by narrowing the spread to the IOER.

If money market funds could have indefinite access to the O/N RRP at, say, 10bp under the IOER, they would not be tempted to move into commercial paper when the Federal Reserve finally starts rising interest rates. However, in order for the Federal Reserve to have enough assets to satisfy money market demand they cannot sell their current holdings of TSYs. The authors actually suggest swapping MBS holdings for additional TSYs and keep the balance sheet constant at current level.

While elegantly presented, there are several problems with this line of argumentation. First of all it is probably only a thinly veiled attempt to justify keeping the balance sheet at current level as selling trillions of TSYs could potentially create problems as longer dated benchmark rates would move higher, far higher.

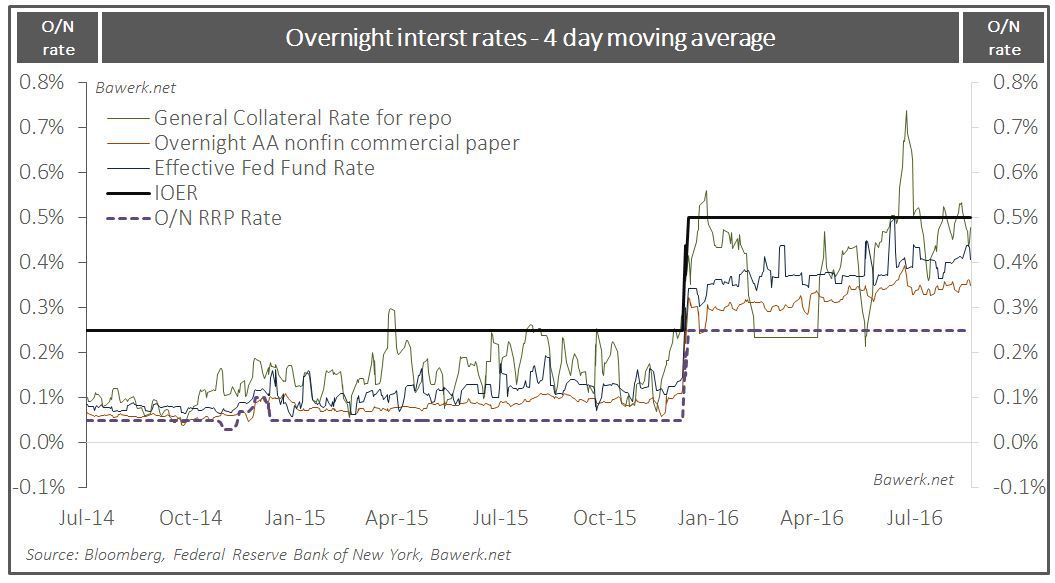

Secondly, it is not supposed to be the Federal Reserve’s job to allocate flow of funds in the economy (stop laughing, we said “supposed”), but that is the job of congressionally approved regulations. And the Securities Exchange Commission (SEC) has actually led reforms of money market mutual funds in this very direction. New regulations that will be fully implemented by October 14 this year force prime funds to mark to market and even impose redemption fees on investors if liquid assets fall below a certain threshold. Prime funds can even stop redemptions completely for up to 10 days if the threshold is broken. Money market funds investing in government paper are not liable for the new regulations. Needless to say, money market flows have reacted accordingly as the whole idea of investing in money market funds is to retain liquidity.

Since October 2015 prime funds have lost almost $570 billion, while government funds have seen close to $700 billion of inflows. The Libor – OIS spread has thus widened considerably as short term funding for financials and companies have become relatively scarcer whilst government funding options have become more than plentiful.

And even though the O/N RRP is at a disadvantage in terms of yield, money market funds still scramble to get into it as they window dress their balance sheet at quarter- and yearend. As the prime funds lose investors, we should expect this stampede to peter out soon enough.

Third, the treasury could in theory just issue enough T-bills to satisfy the need for short-term safe assets. While this alone affects the overall maturity profile, a corresponding lengthening of longer-dated bond issuance would suffice to maintain whatever duration deemed prudent. Note that the consolidated interest rate risk will not be affected whether it is borne by the central bank or the treasury. However, and the authors do have a point, in that the treasury bear someauction risk as rolling over large amounts T-bills every week could potentially lead to hiccups which the Federal Reserve, issuer of legal tender, would not need worry about.

In summary, we are seeing efforts to justify the excessively large balance sheet held by the Federal Reserve and we expect arguments like the one presented above to gain traction. Bear in mind that if the Federal Reserve chose to go along with a $4.5 trillion ledger, the next recession, which will guaranteed start from a very low Fed Funds rate, will be fought with another $2 – 4 trillion worth of asset purchases. In short order, the Federal Reserve will have a balance sheet of more than $8 trillion; if global confidence in the dollar can withstand such folly.