Some commentators are of the view that the present monetary framework is instrumental for the emergence of the so-called money multiplier. Consider the case that banks are legally permitted to hold only 10% in reserves against their demand deposits. In this framework, banks could lend out part of the deposited money thereby setting in motion the money multiplier. For instance, against a deposit of $100 bank A will lend $90. Let us say that the $90 will end up with the Bank B, which will lend 90% of the $90. The $81 will end up with a third bank, which in turn will lend out 90% of $81 and so on. Consequently, this process will result in the expansion of demand deposits to $1,000. If previously the amount of money stood at $100 – held in demand deposit – so now it is $1,000 held in demand deposits.

Fractional reserve banking and creation of money

When Tom lends his $100 to Mike this type of transaction doesn’t create new money since Tom just transfers his $100 for the period of the loan to Mike. This type of transaction temporarily transfers the ownership over the $100 from Tom to Mike.

Likewise when a bank mediates between Tom and Mike i.e. it borrows from Tom $100 and lends these $100 to Mike the bank does not create new money.

Similarly, if the bank lends $1 million, which was obtained by issuing stocks to this amount-no new money was created. People who bought bank’s stocks have paid with their money, which in turn the bank employs in its lending activities. Note that lending here does not give rise to the creation of new money.

The so-called multiplier arises as a result of the fact that banks are legally permitted to use money that is placed in demand deposits. Banks treat this type of money as if it was loaned to them.

If John places $100 in demand deposit at Bank One he doesn’t relinquish his claim over the deposited $100. He has unlimited claim against his $100. The demand deposit must be regarded as not different from the safe deposit box. (Note that John can exercise his demand for money by either holding money in his pocket, or under his mattress, or in the safe deposit box, or in bank demand deposit).

Hence when Bank One uses the deposited money as if they were loaned to him the bank in fact violates individual’s property right. It is not different from taking some of the money that an individual stored in the safe deposit box without the individual agreement. Note that once bank lends some of the deposited money the bank generates new deposit and in turn another claim.

For instance, let us say that Bank One lends $50 to Mike. By lending Mike $50, the bank creates a deposit for $50 that Mike can now use. Remember that John still has a claim against $100 while Mike has now a claim against $50.

This type of lending is what fractional reserve banking is all about. The bank has $100 in cash against claims, or deposits of $150. The bank therefore holds 66.7% reserves against demand deposits. The bank has created $50 out of “thin air” since these $50 are not supported by any genuine money.

Now Mike buys for $50 goods from Tom and pays Tom by check. Tom places the check with his bank, Bank B. After clearing the check, Bank B will have an increase in cash of $50, which he may take advantage of and lend out part of it let us say $25 to Bob.

As one can see the fact that banks make use of demand deposits whilst the holders of deposits did not relinquish their claims sets in motion the money multiplier.

A case could be made that people who place their money in demand deposits do not mind banks using their money. We hold that if an individual has a demand for money then he cannot at the same time not to have a demand for money.

Hence, if against individuals’ demand for money, which is expressed through a demand deposit, the bank lends out a part of the deposited money, an unbacked lending must emerge i.e. money out of “thin air” is generated.

Regardless of people’s psychological disposition what matters here that individuals did not relinquish their claim on deposited money. Once banks use the deposited money, an expansion of money out of “thin air” is set in motion.

Although the law allows this type of practice, from an economic point of view it produces a similar outcome that any counterfeiter activities do. It results in money out of “thin air” which leads to consumption that is not supported by production i.e. to the dilution of the pool of real wealth.

The legal precedent to the fractional reserve banking was set in England in 1811 in the court case of Carr v. Carr. The court had to decide whether the term “debts” mentioned in a will included a cash balance in a bank deposit account. The Judge, Sir William Grant, ruled that it did. According to Grant, because the money had been paid generally into the bank, and was not earmarked in a sealed bag, it had become a loan to the bank. The Judge also insisted that money deposited with a bank becomes part of bank’s assets and liabilities.[1]

According to Mises,

It is usual to reckon the acceptance of a deposit which can be drawn upon at any time by means of notes or checks as a type of credit transaction and juristically this view is, of course, justified; but economically, the case is not one of a credit transaction……..A depositor of a sum of money who acquires in exchange for it a claim convertible into money at any time which will perform exactly the same service for him as the sum it refers to, has exchanged no present good for a future good. The claim that he has acquired by his deposit is also a present good for him. The depositing of money in no way means that he has renounced immediate disposal over the utility that it commands.[2]

Similarly, Rothbard argued,

In this sense, a demand deposit, while legally designated as credit, is actually a present good – a warehouse claim to a present good that is similar to a bailment transaction, in which the warehouse pledges to redeem the ticket at any time on demand.[3]

Why proper free market will curtail fractional reserve banking

In a truly free market economy the likelihood that banks will practice fractional reserve banking will tend to be very low. If a particular bank tries to practice fractional reserve banking he runs the risk of not being able to honour his checks. For instance if Bank One lends out $50 to Mike out of $100 deposited by John it runs the risk of going bust. Why? Let us say that both John and Mike have decided to exercise their claims. Let us also assume that John buys goods for $100 from Tom while Mike buys goods for $50 from Jerry. Both John and Mike pay for the goods with checks against their deposits with the Bank One.

Now Tom and Jerry are depositing received checks from John and Mike with their bank – Bank B, which is a competitor of Bank One. Bank B in turn will present these checks to Bank One and will demand cash in return. However, Bank One has only $100 in cash – he is short of $50. Consequently, the Bank One is running the risk of going belly up unless it could quickly mobilize the cash by selling some of his assets or by borrowings.

The fact that banks must clear their checks will be a sufficient deterrent to practice fractional reserve banking in a free market economy.

Furthermore, it must be realized that the tendency of being “caught” practicing fractional reserve banking, so to speak, is rising, as there are many competitive banks. As the number of banks rises and the number of clients per bank declines the chances that clients will spend money on goods of individuals that are banking with other banks will increase. This in turn will increase the risk of the bank not being able to honor his checks once this bank practices fractional reserve banking.

Conversely, as the number of competitive banks diminishes, that is as the number of clients per bank rises the likelihood of being “caught” practicing reserve banking is diminishes. In the extreme case if there is only one bank it can practice fractional reserve banking without any fear of being “caught” so to speak.

Thus if Tom and Jerry are also the clients of the Bank One then once they will deposit their received checks from John and Mike, the ownership of deposits will be now transferred from John and Mike to Tom and Jerry. This transfer of ownership however, will not cause any effect on the Bank One.

We can then conclude that in a free market if a particular bank tries to expand credit by practicing fractional reserve banking he is running the risk of being “caught”. Hence in a true free market economy the threat of bankruptcy will bring to a minimum the practice of fractional reserve banking.

Central Bank and fractional reserve banking

Whilst in a free market economy the practice of fractional reserve banking would tend to be minimal, this is not so in the case of the existence of the central bank.

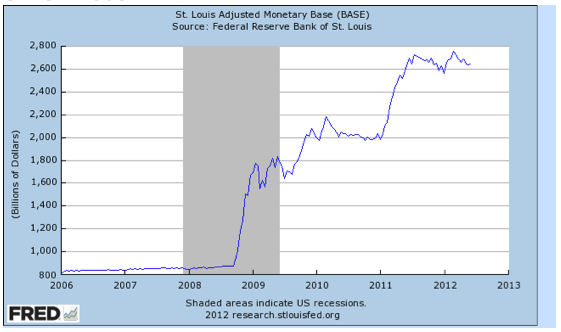

By means of monetary policy, which is also labelled as reserve management of the banking system the central bank supports the existence of the fractional reserve banking and thus the creation of money out of “thin air”.

The modern banking system can be seen as one huge monopoly bank which is guided and coordinated by the central bank. Banks in this framework can be regarded as branches of the central bank. For all the intent and purposes the banking system can be seen as comprising of one bank. (As we have seen a monopoly bank can practice fractional reserve without running the risk of being “caught”).

Through the ongoing monetary management i.e. monetary pumping the central bank makes sure that all the banks could engage jointly in the expansion of credit out of “thin air”, through the practice of fractional reserve banking. The joint expansion in turn guarantees that checks presented for redemption by banks to each other are netted out.

By means of the monetary injections the central bank makes sure that the banking system is “liquid enough” so banks will not bankrupt each other.

Whenever the Fed injects money to the system this will result in an increase in a deposit of a particular bank. This bank, based on his portfolio strategy, will decide how much of this increase in deposits it will lend out and how much it will keep in reserves. (Even in the modern banking system banks would have to keep certain amount of reserves in order to settle transactions).

Now, if a bank decides to keep 20% in reserves against the new increase in deposits then it will lend out 80% of these new deposits.

For instance, as a result of the Fed’s monetary injections Bank One deposits increased by $1 billion and the bank lends $800 million whilst the rest kept in reserves. Let us assume that the borrowers of $800 million are buying goods from individuals that bank with Bank B who in turn presents checks for clearance on this amount to Bank One. Since Bank One has in his possession $1 billion it would have no problems to clear the check.

Consider however, a case that Bob deposited $100 with Bank One. The bank decides to lend 80% to Mike whilst the rest is kept in cash reserves. A problem could emerge if both Bob and Mike were to decide to take their money out . Then there is a risk that Bank One will not be able to honour his checks. In the event of such occurrence, the Fed is ready to provide Bank One with a loan to prevent bankruptcy. (Furthermore, by making sure that the banking system has enough money the central bank enables the bank that encounters difficulties to honour its checks by borrowing in the so- called money market).

Also, note that the fractional reserve banking is inherently unstable. The time structure of banks assets is longer than the time structure of its liabilities. Banks demand deposits – liabilities – are due instantly, on demand, while its outstanding loans to debtors are for a longer period. (Additionally note that the presence of the central bank encourages banks to fund long term assets with short term money thereby running into possible financial difficulties once short term interest rates rising above the long term interest rates).

According to Rothbard,

A bank is always inherently bankrupt, and would actually become so if its depositors all woke up to the fact that the money they believe to be available on demand is actually not there.[4]

Finally, not only does fractional reserve banking gives rise to monetary inflation it is also responsible for monetary deflation. Since banks by means of fractional reserve banking generate money out of “thin air” whenever they do not renew their lending they in fact give rise to the disappearance of money.

This must be contrasted with the lending of genuine money, which can never physically disappear unless it is physically destroyed. Thus when John lends his $50 via Bank One to Mike the $50 is transferred to Mike from John. On the day of the maturity of the loan Mike transfers to the Bank One $50 plus interest. The bank in turn transfers the $50 plus interest adjusted for bank fees to John – no money has disappeared.

If however, the Bank One practices fractional reserve banking it lends the $50 to Mike out of “thin air”. On the day of the maturity when Mike repays the $50 the money goes back to the bank the original creator of this empty money i.e. money disappears from the economy, or it vanishes into the “thin air”.

Conclusions

The existence of the central bank enables banks to practice fractional reserve banking, which sets in motion the so-called money multiplier. This in turn gives rise to inflationary credit and the menace of the boom-bust cycles.

[1] Murray N. Rothbard, The Mystery of Banking

[2] Ludwig von Mises 1980, The Theory of Money and Credit. Indianopolis, Ind: Libery Classics( pp300-01).

[3] Murray N. Rothbard 1978, Austrian definitions of the supply of money, in New Directions in Austrian Economics p 148.

[4] Murray N. Rothbard, The Mystery of Banking, p 99.

Agreed, Frank.

For clarity’s sake it’s perhaps worth also mentioning what seems to be Mises’ conclusion regarding FRB. I’m sure you’re more than familiar with the following quote from Human Action but some other readers here may not be:

“But even if the 100 percent reserve plan were to be adopted on the basis of the unadulterated gold standard, it would not entirely remove the drawbacks inherent in every kind of government interference with banking. What is needed to prevent any further credit expansion is to place the banking business under the general rules of commercial and civil laws compelling every individual and firm to fulfil all obligations in full compliance with the terms of the contract. [ . . . ]

Free banking is the only method available for the prevention of the dangers inherent in credit expansion. It would, it is true, not hinder a slow credit expansion, kept within very narrow limits, on the part of cautious banks which provide the public with all information required about their financial status. But under free banking it would have been impossible for credit expansion with all its inevitable consequences to have developed into a regular – one is tempted to say normal – feature of the economic system. Only free banking would have rendered the market economy secure against crises and depressions.”