Ten years ago, before the collapse of Lehman Brothers rocked global financial markets, the Fed’s balance sheet stood at $925 billion—mostly U.S. Treasuries. After fifty-nine months of asset purchases to push down longer-term interest rates, it had ballooned to a peak of $4.5 trillion, including nearly $1.8 trillion in mortgage securities, in October 2014.

In October of this year, the Fed at last began a slow slimming-down of the balance sheet, allowing $10 billion in maturing securities to roll off without reinvesting the proceeds. All else being equal, this represents a tightening of monetary policy, as it tends to push up longer-term (10-year) market interest rates.

In Fed chair Janet Yellen’s words, the central bank “does not have any experience in calibrating the pace and composition of asset redemptions and sales to actual prospective economic conditions.” She has therefore stressed that the Fed sees its balance-sheet reduction as a primarily technical exercise separate from the pursuit of its monetary policy goals—in particular, pushing inflation back up to 2%. The Fed’s main tool for tightening monetary policy in a recovering economy would, therefore, she explained, be raising short-term market interest rates by paying banks greater interest on reserves (IOR). Since December 2015, the Fed has raised the rate on IOR by 100 basis points (1%), which has pushed up its short-term benchmark rate—the effective federal funds rate—in tandem.

But is Yellen right that the Fed’s gradual approach to balance-sheet reduction makes it relatively unimportant in its impact on monetary conditions? Our analysis suggests that it will be, in fact, considerably more important than the market, or the Fed itself, realizes. Here is why.

Longer-term bond yields in the market, which the Fed is looking to nudge upward as it tightens policy, can be separated into two components. The first is the expected path of short- term interest rates. Changes in the Fed’s policy rate, its guidance about the pace of rate hikes, and the economic outlook all affect the expected path of short-term interest rates.

The second is a term premium, which is the compensation that investors require for holding a longer-term bond (as opposed to rolling over short-term bonds for the equivalent length of time). The term premium fluctuates with supply and demand for particular bonds. The Fed’s accumulation of longer-term Treasuries during nearly five years of Quantitative Easing (QE) was a big source of demand and therefore lowered the term premium on longer-term Treasuries. (Former Fed Chair Ben Bernanke explains this well in his blog.) Fed economists estimate that yields on 10-year Treasuries would today be around 85 basis points higher than their current level of 2.3% had the Fed not bought such bonds.

Yellen acknowledges that reducing the balance sheet now is, logically, a substitute for raising the Fed’s policy rate. More of one should, therefore, mean less of the other, and vice- versa. But what are the trade-offs?

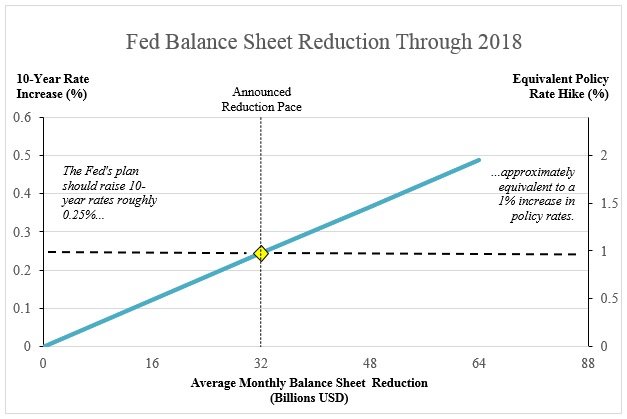

On the basis of those Fed-economist estimates above, we calculate that the Fed’s plan to reduce the balance sheet by $450 billion from this October through the end of 2018 (a monthly average of about $32 billion) is roughly equivalent to a one percent hike in the policy rate—as we illustrate in the figure below. This equivalence means that the effective federal funds rate at the end of 2018 should be a full percentage point lower than it would be without the balance-sheet reduction. That’s a big number.

CFR

CFR

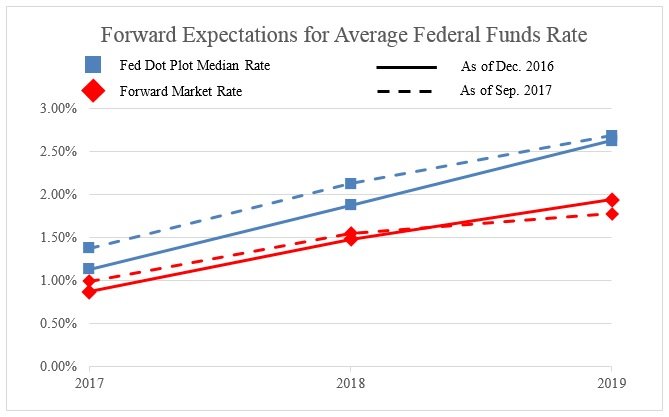

Does the market realize this? Does the Fed? The data suggest not. The Fed announced its plans for balance-sheet reduction back in June. Since then, market estimates of the effective federal funds rate through 2019 have moved little from pre-announcement levels, and in fact have risen slightly—as we show below. Likewise, the “dot plot” rate projections of Federal Open Market Committee members have hardly budged since the end of last year. Unless both the market and the Fed suddenly became vastly more sanguine about growth prospects at the time of the announcement, these facts suggest that they are largely ignoring — and therefore greatly underestimating—the tightening impact of the balance-sheet reduction.

CFR

CFR

What does this mean, going forward? It means that the Fed is likely to push rates higher than they should over the coming year. And if that is right, the risks of slower-than-expected growth are also higher.

Benn Steil is director of international economics at the Council on Foreign Relations and author of The Marshall Plan: Dawn of the Cold War. Benjamin Della Rocca is an analyst at the Council.