- Emerging market stocks have stabilised, helped by the strength of US equities

- Rising emerging market bond yields are beginning to attract investor attention

- US tariffs and domestic tax cuts support US economic growth

- US$ strength is dampening US inflation, doing the work of the Federal Reserve

To begin delving into the recent out-performance of the US stock market relative to its international peers, we need to reflect on the global fiscal and monetary response to the last crisis. After the great financial recession of 2008/2009, the main driver of stock market performance was the combined reduction of interest rates by the world’s largest central banks. When rate cuts failed to stimulate sufficient economic growth – and conscious of the failure of monetary largesse to stimulate the Japanese economy – the Federal Reserve embarked on successive rounds of ‘experimental’ quantitative easing. The US government also played its part, introducing the Troubled Asset Relief Program – TARP. Despite these substantial interventions, the velocity of circulation of money supply plummeted: and, although it had met elements of its dual-mandate (stable prices and full employment), the Fed remained concerned that whilst unemployment declined, average earnings stubbornly refused to rise.

Eventually the US economy began to grow and, after almost a decade, the Federal Reserve, cautiously attempted to reverse the temporary, emergency measures it had been forced to adopt. It was helped by the election of a new president who, during his election campaign, had pledged to cut taxes and impose tariffs on imported goods which he believed were being dumped on the US market.

Europe and Japan, meanwhile, struggled to gain economic traction, the overhang of debt more than offsetting the even lower level of interest rates in these markets. Emerging markets, which had recovered from the crisis of 1998 but adopted fiscal rectitude in the process, now resorted to debt in order to maintain growth. They had room to manoeuvre, having deleveraged for more than a decade, but the spectre of a trade war with the US has made them vulnerable to any strengthening of the reserve currency. They need to raise interest rates, by more than is required to control domestic inflation, in order to defend against capital flight.

In light of these developments, the recent divergence between developed and emerging markets – and especially the outperformance of US stocks – is understandable. US rates are rising, elsewhere in developed markets they are generally not; added to which, US tariffs are biting, especially in mercantilist economies which have relied, for so many years, on exporting to the ‘buyer of last resort’ – namely the US. Nonetheless, the chart below shows that divergence has occurred quite frequently over the past 15 years, this phenomenon is likely to be temporary: –

Source: MSCI, Yardeni Research

Another factor is at work, which benefits US stocks, the outperformance of the technology sector. As finance costs have fallen, to levels never witnessed in recorded history, it has become easier for zombie companies to survive, crowding out more favourable investment opportunities, but it has also allowed, technology companies, with no expectation of near-term positive earnings, to continue raising capital and servicing their debts for far longer than during the tech-bubble of the 1990’s; added to which, the most successful technology companies, which evolved in the aftermath of the bursting of the tech bubble, have come to dominate their niches, often, globally. Cheap capital has helped prolong their market dominance.

Finally, capital flows have played a significant part. As emerging market stocks came under pressure, international asset managers were quick to redeem. These assets, repatriated most often to the US, need to be reallocated: US stocks have been an obvious destination, supported by a business-friendly administration, tax cuts and tariff barriers to international competition. These factors may be short-term but so is the stock holding period of the average investment manager.

Among the most important questions to consider looking ahead over the next five years are these: –

- Will US tariffs start to have a negative impact on US inflation, economic growth and employment?

- Will the US$ continue to rise? And, if so, will commodity prices suffer, forcing the Federal Reserve to reverse its tightening as import price inflation collapses?

- Will the collapse in the value of the Turkish Lira and the Argentine Peso prompt further competitive devaluation of other emerging market currencies?

In answer to the first question, I believe it will take a considerable amount of time for employment and economic growth to be affected, provided that consumer and business confidence remains strong. Inflation will rise unless the US$ rises faster.

Which brings us to the second question. With higher interest rates and broad-based economic growth, primed by a tax cut and tariffs barriers, I expect the US$ to be well supported. Unemployment maybe at a record low, but the quality of employment remains poor. The Gig economy offers workers flexibility, but at the cost of earning potential. Inflation in raw materials will continued to be tempered by a lack of purchasing power among the vastly expanded ranks of the temporarily and cheaply employed.

Switching to the question of contagion. I believe the ramifications of the recent collapse in the value of the Turkish Lira will spread, but only to vulnerable countries; trade deficit countries will be the beneficiaries as import prices fall (see the table at the end of this letter for a recent snapshot of the impact since mid-July).

At a recent symposium hosted by Aberdeen Standard Asset Management – Emerging Markets: increasing or decreasing risks? they polled delegates about the prospects for emerging markets, these were their findings: –

83% believe risks in EMs are increasing; 17% believe they are decreasing

46% consider rising U.S. interest rates/rising U.S. dollar to be the greatest risk for EMs over the next 12 months; 25% say a slowdown in China is the biggest threat

50% believe Asia offers the best EM opportunities over the next 12 months; 20% consider Latin America to have the greatest potential

64% believe EM bonds offer the best risk-adjusted returns over the next three years; 36% voted for EM equities.

The increase in EM bond yields may be encouraging investors back into fixed income, but as I wrote recently in Macro Letter – No 99 – 22-06-2018 – Where in the world? Hunting for value in the bond market there are a limited number of markets where the 10yr yield offers more than 2% above the base rate and the real-yield is greater than 1.5%. That Turkey has now joined there ranks, with a base rate of 17.75%, inflation at 15.85% and a 10yr government bond yield of 21.03%, should not be regarded as a recommendation to invest. Here is a table looking at the way yields have evolved over the past two months, for a selection of emerging markets, sorted by largest increase in real-yield (for the purposes of this table I’ve ignored the shape of the yield curve): –

Source: Investing.com

Turkish bonds may begin to look good value from a real-yield perspective, but their new government’s approach to the imposition of US tariffs has not been constructive for financial markets: now, sanctions have ensued. With more than half of all Turkish borrowing denominated in foreign currencies, the fortunes of the Lira are unlikely to rebound, bond yields may well rise further too, but Argentina, with inflation at 31% and 10yr (actually it’s a 9yr benchmark bond) yielding 18% there may be cause for hope.

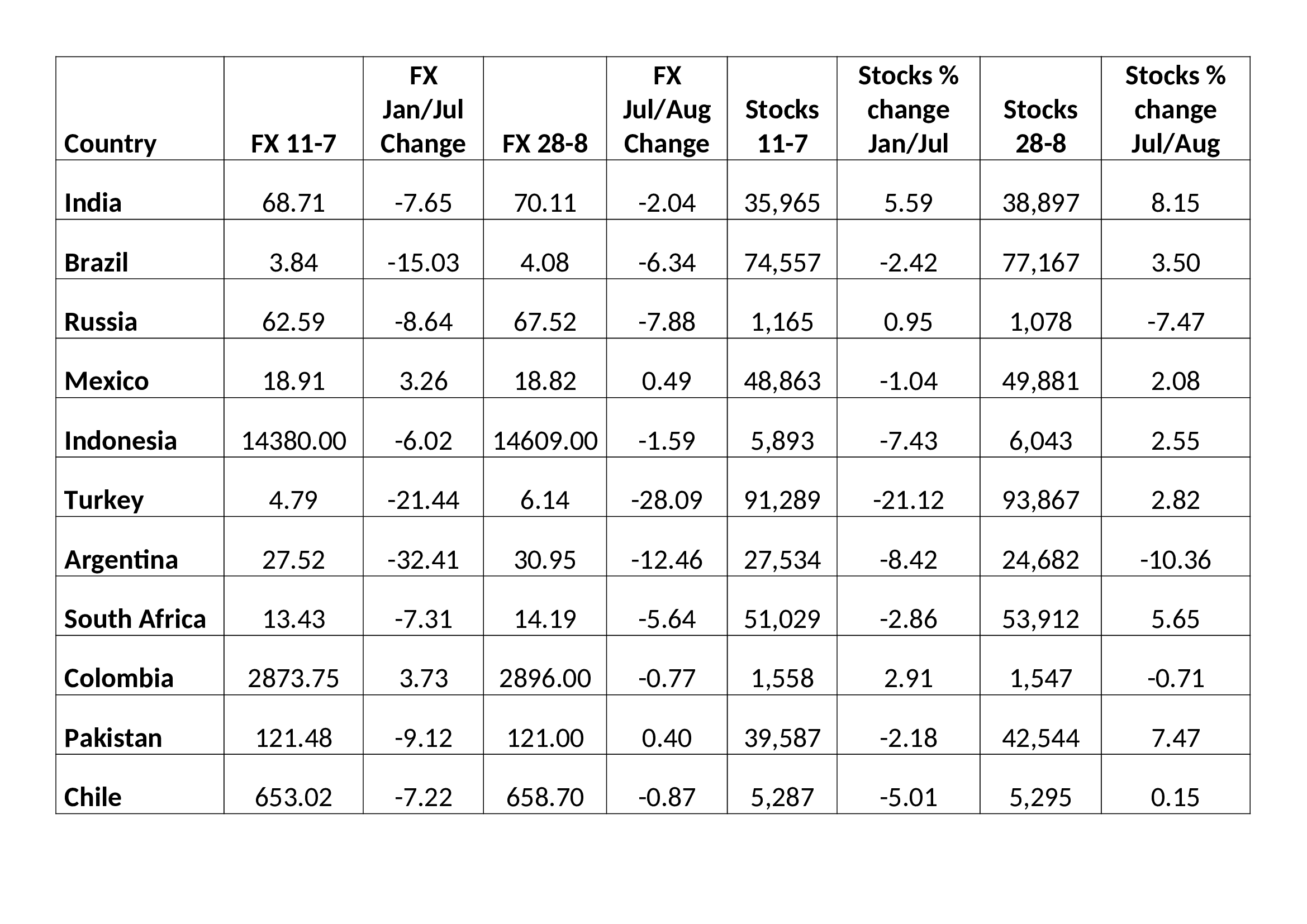

Emerging market currencies have been mixed since July. The Turkish Lira is down another 28%, the Argentinian Peso by 12%, Brazilian Real shed 6.3% and the South African Rand is 5.7% weaker, however the Indonesian Rupiah has declined by just 1.6%. The table below is updated from Macro Letter 100 – 13-07-2018 – Canary in the coal-mine – Emerging market contagion. It shows the performance of currencies and stocks in the period January to mid-July and from mid-July to the 28th August, the countries are arranged by size of economy, largest to smallest: –

Source: Investing.com

It is not unusual to see an emerging stock market rise in response to a collapse in its domestic currency, especially where the country runs a trade surplus with developed countries, but, as the US closes its doors to imports and growth in Europe and Japan stalls, fear could spread. Capital flight may hasten a ‘sudden stop’ sending some of the most vulnerable emerging markets into a sharp and painful recession.

Conclusions and Investment Opportunities

My prediction of six weeks ago was that Turkey would be the market to watch. Contagion has been evident in the wake of the decline of the Lira and the rise in bond yields, but it has not been widespread. Those countries with twin deficits remain vulnerable. In terms of stock markets Indonesia looks remarkably expensive by many measures, India is not far behind. Russia – and to a lesser extent Turkey – continues to appear cheap… ‘The markets can remain irrational longer than I can remain solvent,’ as Keynes once said.

Emerging market bonds may recover if the Federal Reserve tightening cycle is truncated. This will only occur if the pace of US economic growth slows in 2019 and 2020. Another possibility is that the Trump administration manage to achieve their goal, of fairer trading arrangements with China, Europe and beyond, then the impact of tariffs on emerging market economies may be relatively short-lived. The price action in global stock markets have been divergent recently, but the worst of the contagion may be past. Mexico and the US have made progress on replacing NAFTA. Other countries may acquiesce to the new Trumpian compact.

The bull market in US stocks is now the longest ever recorded, it would be incautious to recommend stocks except for the very long-run at this stage in the cycle. In the near-term emerging market volatility should diminish and over-sold markets are likely to rebound. Medium-term, those countries hardest hit by the recent crisis will languish until the inflationary effects of currency depreciations have fed through. In the Long Run, a number of emerging markets, Turkey included, offer value: they have demographics on their side.