Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player who struts and frets his hour upon the stage and then is heard no more.

-Macbeth

Our limited time, our brief candle as Shakespeare’s Macbeth had it earlier in the soliloquy quoted from above, may count for very little in the grand scheme of things, but is of the utmost importance to each of us personally. Unlike the other dimensions, height, breadth and depth, the fourth is almost infinite, but individuals enjoy only a small part of it, our three-score years and ten. Time moves on. What really matters is not wasting it.

We may appear to others to be wasting time. But it is not wasting it when we take a break, recharge our batteries, or stop to think. Pleasure-seeking, pursuing happiness, removing uneasiness is making good use of time. We are all different and enjoy different things, so wasting time is not time wasted so long as it our personal choice. No one can allocate time as effectively as the individual. It is intensely personal.

While using time effectively is a private pleasure, wasting it can be very frustrating. Wasting time is the denial of personal ambition, whether it is as trivial as in a game of cards or as momentous as changing one’s circumstances. Avoiding time-wasting requires positive personal action, but we live in a world where that decision is progressively being subsumed by the state. But the state has little concept of the importance of time, replacing it with indecision and deferment. Time offers change and progress, except to the state. The evolution of events that go with time undermines the state’s certainties. The state believes it has all the time in the world to get things right by consulting, reporting, debating and eventually acting, while everyone affected has to wait.

It takes more than a decade to agree a trade deal between the EU and another government, neither of which feels time is important. This snail’s pace with our time is the norm in government and inter-governmental affairs. In business, time is a cost working against profit, because profit is always measured within a time-frame. A businessman who is both proficient and efficient is a valued person in society. He is productive, maximising profits while limiting the time spent achieving them. Time is also the basis of interest rates, which far from being a cost of money, is an expression of time preference. Time preference is the discounted future value of materials, energy and effort not yet in possession, but promised to be so at a given future date.

Through monetary policy the state commandeers our time preferences, forcing its own omnibus version upon us. It commands the value of our personal futures relative to cash. We don’t often realise how damaging is the loss of freedom to determine the fourth dimension for ourselves. If we understood the state was depriving us of time, we would probably be angry. The embezzlement of its use is behind the growing frustration felt by ordinary people. It is the underlying theme to Hayek’s Road to Serfdom, how the state conspires to steal its people’s freedom for statist priorities.

The state’s functionaries are usually ignorant of what they are doing. As stated above, wasting our time doesn’t matter to them. It has taken two and a half years for the British Government to fail to negotiate Brexit, wasting every citizens’ time in both Britain and the EU wanting certainty.

The statists don’t care, because they place little or no value on time. The vade mecum which is their ultimate guide in these matters, Keynes’s General Theory, makes no substantive mention of the meaning of time until Page 293, where he correctly states that “the importance of money essentially flows from it being the link between the present and the future” [ italics in the original][i].

It is one thing that Keynes actually got right, but he then ignored the implications. The time dimension does not sit well with Keynes’s mathematical approach to economics, because the assumption behind equations is that time does not alter them. A+B@C can only assume all components are unaffected by time. In reality, a static world where yesterday’s deployment of money replicates tomorrow’s deployment of money, does not exist. If it did, there would be no human progress. Therefore, time brings with it change, so is an inconvenience which the neo-Keynesians choose to ignore.

Clearly, the statists’ motivation was to discard proven classical theory to make way for propositions that favoured the state controlling money, which as Keynes pointed out is the bridge between the present and the future. First, we produce. Then we are paid. Then we spend and save. Money is the temporary storage of our labour for future use. Time and money are synonymous and common to all these activities.

We think the state is taking only our money, but it is also taking our time. If it was more widely appreciated that we are being robbed of our time, attitudes towards state intervention would surely change. As it is, we think it is only money, and surely, who would want to be thought of as so venal to object to its redistribution to those that deserve it more?

Create a credit cycle, then suppress the consequences

The state has been extremely effective at picking our pockets, employing monetary prestidigitation as well as taxes. By taking control of the economic and monetary agenda, the state has persuaded us it can deploy our money more effectively than we can ourselves. It commands us to exclusively use the state’s own currency, backed by our faith in its credit. It suppresses interest rates to grow the economy and maximise taxes, saying we can become better off together. It takes payments from us and spends them in a manner determined by the state acting in our collective interest.

When the theft of our time is relatively minor, we tolerate it. We can grow wealthier together. But when we find ourselves working increasingly for the state, spending almost half our working lifetime doing so, our discontent and resentment builds. We are no longer in control of the fruits of our labour, our time. The central bank then springs to our rescue, creating the extra money we have lost in taxes, and encouraging the banks it regulates to extend credit to allow us to make more and spend more. It debases both our time preferences and the true cost of our wages to our employers. For a brief period, it might appear to work, so long as the losers don’t notice and complain. But it leads to economic instability by replacing the healthy randomness of our collective desires with a cycle of credit expansion and contraction.

Earnings and savings, the fruits of our time spent, are transferred from ordinary citizens and gifted to others favoured by the state, simply by suppressing interest rates, thereby reducing time preferences. Time-value is taken from consumers and given to producing borrowers. Over the decades, consumers have been gradually impoverished, and producers have learned to love the state more than the consumer.

Our inept leaders can sincerely believe they are making a better world for us all, but they suppress the evidence when it goes wrong. Instead of making a better world, over time they have depleted personal wealth and earnings by taxes and monetary debasement, leaving little left to transfer to the state in future. But time is money, so the state simply prints yet more currency to buy more time. In the absence of time-pressures the state believes the future can be deferred indefinitely, and eventually everything will be all right. Just be patient and give us more of your time…

Are we any happier without our stolen time? Occupy Wall Street, the emergence of America’s Despicables, Britain’s Brexiteers and France’s rioters all attest otherwise. Now that savings have been depleted, we must borrow to spend. The yellow brick road, which the stealers of our time promised will lead to only good things, is leading us instead into destitution.

The theft of time ends in a credit-driven crisis

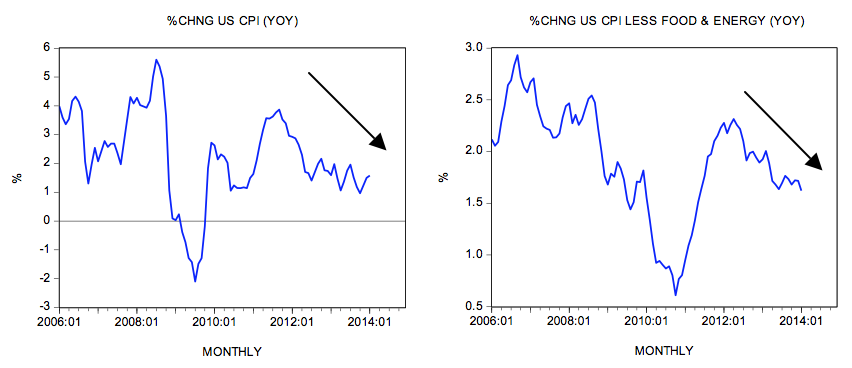

The theft of our time through monetary debasement has continued apace ever since the discipline of gold was removed from the global monetary system. This occurred in steps from the early 1930s but accelerated after the Nixon shock in 1971. Prices then began to rise rapidly, as money’s purchasing power declined. The state eventually found a solution to rising prices: it just denies they are happening. The contents of consumer price index is continually rotated and adjusted, which in effect goal-seeks a modest two per cent annual rise.

In the 1980s governments came up with a new wheeze to augment declining savings: lend money to savers through the banks in order to inflate assets and consumption. They did this by repealing the Glass-Steagall legislation, which separated investment banking from commercial lending. Credit became increasingly available for residential property, credit cards and personal loans. The banks gained economic power and profits by creating this credit out of thin air and bankers made fortunes for themselves.

Since the 1980s, the destruction of genuine savings has been offset by the asset inflation fuelled through this easy credit. The excesses led to the 1987 crash, the dot-com bubble in 2000, and the residential property bubble in 2006-07. But the downs in property and financial asset prices were always rescued by yet more credit. Following the Lehman crisis ten years ago, the debasement of money has accelerated, asset prices have inflated, and price inflation has been concealed by the goal-seeking CPI.

The lack of any constancy in the currency allows the state to act without the bulk of the population being aware it is being robbed of its earnings, its savings, its future, its time. The simple truth is that not only is everyone poorer than they might have otherwise been, but they are poorer in absolute terms as well. Every year, the public is robbed some more, to the point where eventually there will be very little left to give, relative to the state’s escalating demands.

We must be close to that point. Only this week, we have seen the Christmas trade in Britain fail. Falling bank shares are an ominous leading indicator. Everywhere, people are less keen to borrow the credit offered by motor manufacturers to finance the purchase of their cars. Credit cards are maxed out. Homeless numbers in England, the ultimate indicator of personal distress, are up 169% since 2010.[ii] Additionally, tariffs, which are consumer taxes and taxes on production, are being imposed on Americans leaving them poorer.

The inevitable and forthcoming crisis is taking us to the end of that yellow brick road. We are not going out in a speculative bang, but with an impoverished whimper, with nothing left to give. And when the state collects diminished returns through taxes, it always seeks to recover them through yet more monetary debasement.

We know it ends in crisis, because history and logic say so. We appear to be on the verge of it, because of the message from the markets. Corporate bond markets in both America and the EU are in a stasis.[iii] We are also told that US banks are pulling the rug on corporate loans.[iv]

They call this deflationary, an imprecise term, which as Humpty Dumpty said, “it means what I choose it to mean”. A better description for what is happening is that it is the consequence of an accumulating and continual theft of peoples’ time by the state through the unfettered issuance of money and credit. Calling it deflation encourages the state’s agents to debase the currency even further, in the naïve belief that it is the antonym of inflation.

Stock markets are now falling, because investors are suspending their belief that the state is in control and can avoid deflation while steering us into a promised land of perpetually rising asset values. But when investors begin to think, as opposed to believe, the awkward questions will start coming. If the currency is being debased, the state will have to borrow escalating quantities of its own money just to stand still. And since the state has taken responsibility for our welfare, in a recession (another of Humpty Dumpty’s imprecise words) the state will have to borrow even more.

Where will the money come from? And at what interest rates? If borrowing costs are rising because we have nothing left to fund escalating state commitments, what of the corporations that calculate their returns based on the rising cost of working capital? Have bond markets and bank lending seized up because the banks have thrown in the towel? Having taken command of our time-preferences, has the state itself finally lost control?

It is only faith that allowed us to believe otherwise. Faith in the state, and faith in its credit. Without that, the state’s unbacked money loses its purchasing power, wasting all that time the state has taken from us. We can redefine the upcoming inflationary slump as being simply the visible destruction of everyone’s time.

[i] JM Keynes. The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money Palgrave Macmillan reprint 2007

[ii] https://www.homeless.org.uk/facts/homelessness-in-numbers/rough-sleeping/rough-sleeping-our-analysis