The US debt ceiling suspension, signed on February 2018, expires in March this year. According to some experts, the US Treasury will have to carry out special measures because of possible delays in raising this ceiling. Treasury would need to draw down its deposits with the Fed and deposit the money in various banks for future use to pay government expenses. As a result, this would boost monetary liquidity and therefore would have beneficial effects on financial markets.

It is sometimes argued that changes in government deposits with the Federal Reserve (Fed) set in motion changes in liquidity and that this has effects on financial markets. On this logic an increase in government deposits with the Fed would lead to a decline in the supply of money and hence to a decline in monetary liquidity.

Conversely, a decline in government deposits with the central bank results in an increase in money supply and monetary liquidity. An implicit assumption in this logic is that an increase in money supply and an increase in liquidity represent the same thing.

The meaning of monetary liquidity

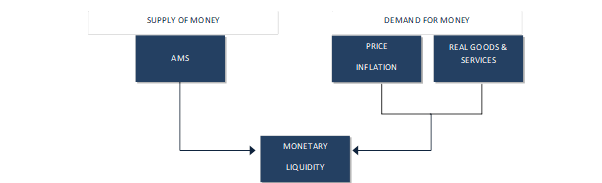

Whilst many people talk about money and liquidity interchangeably, the reality is these are both very different concepts. Whilst the term money simply refers to the supply of money, the term liquidity relates to the interplay between the supply of and the demand for money.

People demand money primarily in order to facilitate trade. By means of money, a product of one specialist is exchanged for the product of another specialist. The nub of what makes a particular thing money (i.e. a medium of exchange) is that it offers to its holder a greater purchasing power than any other good. Money (being the most marketable entity) enables an individual to secure a greater variety of goods than any other good could do i.e. it has a much greater purchasing power. Therefore, when people seek more money they do not want more money in their pockets but, rather, more purchasing power.

According to Mises,

The services money renders are conditioned by the height of its purchasing power. Nobody wants to have in his cash holding a definite number of pieces of money or a definite weight of money; he wants to keep a cash holding of a definite amount of purchasing power.[1]

When the central bank embarks on loose monetary policy then, for any given level of purchasing power and demand for money, the increase in the quantity of money supplied will result in a surplus of money. As a rule, no individual is going to hold more money than is required. Consequently, individuals will attempt to get rid of the surplus of money by converting it into (i.e. buying) goods and services. In the process, this will lift the prices of goods and services i.e. reduce the purchasing power of money. This decline in the purchasing power of money will work towards the equilibration in the quantity of money demanded, with the quantity of money supplied.

Conversely, if (for a given money supply) there is an increase in economic activity as represented by an increase in the production of goods, a likely increase in demand for money emerges i.e. more money is required now to exchange with a greater volume of output. Thus, for a given purchasing power of money, the quantity of money demanded exceeds the quantity of money supplied i.e. a scarcity of money emerges. Given that now we have more goods versus money the prices of goods will decline i.e. the purchasing power of money will increase. At the higher purchasing power of money, the quantity of money demanded is going to be in line with the quantity supplied.

The gap or difference between the growth rates of quantities of money supplied versus demanded we label liquidity. A decline in this gap represents a decline in liquidity whilst an increase in the gap represents an increase in liquidity.

Note that liquidity is the difference between the growth rates of the supply of money versus the demand for money.

Liquidity = % change in supply of money – % change in demand for money

The most common components that drive changes in the demand for money are changes in output and price inflation.

Note again that liquidity emerges once the quantity of money supplied and demanded are out of equilibrium due to the interplay between the supply of and the demand for money. The emergence of liquidity sets in motion an equilibrating process through changes in the prices of goods. Through this process, we can thus see that the change in the purchasing power of money works to equate the quantity of money supplied with the quantity of money demanded i.e. to the elimination of liquidity. In reality, this equilibrium may never be reached what however, matters is the dynamics that pushes towards the equilibrium. This dynamics is set in motion because of the difference between the quantity of money supplied and the quantity of money demanded, which activates changes in the purchasing power of money.

Changes in liquidity affect markets with a time lag

A change in liquidity does not affect all goods and asset prices instantly – there is a time lag. Let us say that a relative increase in the supply of money versus the demand for money takes place. This will set tendencies towards the decline in the purchasing power of money. This resulting increase in liquidity will travel from one market to another market until, on average, the prices of goods increase to the point where the quantity of money supplied equates with the quantity of money demanded. (At the lower purchasing power of money the larger quantity of money supplied will be in line with the quantity demanded).

Conversely, a decline in monetary injections will set tendencies towards an increase in the purchasing power of money and will work towards equating the quantity of money supplied with that demanded. (At the higher purchasing power of money, a smaller quantity of money supplied will be in line with the quantity demanded).

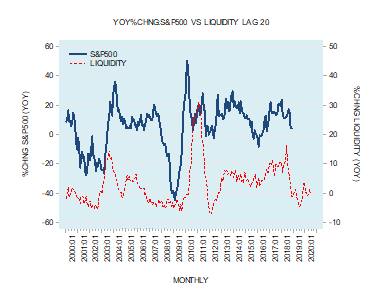

Given that fluctuations in liquidity exert their effect on markets for goods and assets with a time lag, we should expect that changes in the prices of various goods and financial assets would follow changes in liquidity.

Monetary growth and liquidity – are they positively correlated?

Given that liquidity is the product of the interplay between the supply of and the demand for money, it is not necessarily always the case that an increase in money supply leads to an increase in liquidity. Indeed, an increase in the money supply growth rate could be associated with a decline in liquidity. Conversely, it is quite possible that a fall in the money supply growth rate could be associated with a rise in liquidity.

For instance, if the money supply fell by 10% and were accompanied by a decline in economic activity by 10% and a decline in price inflation by 5%, this would then result in an increase in liquidity by 5%, calculated as follows:

Liquidity = -10% – (-10%) – (-5%) = +5%

Historically there have been notable occasions when money supply and liquidity have not moved in tandem. Between October 1929 and July 1932, for example, the yearly growth rate of money supply plunged from 8.3% to minus 14.5% whilst during the same period liquidity increased from 0.2% to 26.5%. In addition, during the period October 1970 to August 1972 the yearly growth rate of money supply increased from 5.5% to 6.1%. During that period, liquidity fell from 6.3% to minus 7.9%.

|

|

|

Assessing prospects for the S&P500 from a liquidity perspective

Even if various commentators are correct and the US economy faces massive increases in money supply growth during Q1 because of government expenditure, we suggest that this may not have a strong impact on financial markets. Because changes in money supply and liquidity affect markets with a lag the trajectory of financial markets in the current (March) quarter is already largely determined by previous changes in liquidity.

With the US, the average time lag between changes in liquidity and changes in financial asset prices is around 20 months. Thus we can suggest that, as a result of changes in liquidity around 20 months ago, the rate of change of the S&P500 is likely to come under downward pressure during much of 2019. Note that this assessment is from a liquidity perspective only.

Conclusions

We suggest that changes in money supply and liquidity are not the same thing. Liquidity is the outcome of the interplay between the supply of and the demand for money. Contrary to commonly held beliefs, it is possible that changes in money supply and liquidity may move in different directions. In addition, we suggest that even if we see strong increases in money supply in Q1, as suggested by some commentators, this is not necessary going to be bullish for the stock market given the likely negative effects of past fluctuations in liquidity.

[1] Ludwig von Mises, Human Action, 3rd rev.ed. (Chicago: Contemporary Books, 1966) p 421.