- The amount of negative yielding fixed securities has hit a new record

- The Federal Reserve and the ECB are expected to resume easing of interest rates

- Secondary market liquidity for many fixed income securities is dying

- Outstanding debt is setting all-time highs

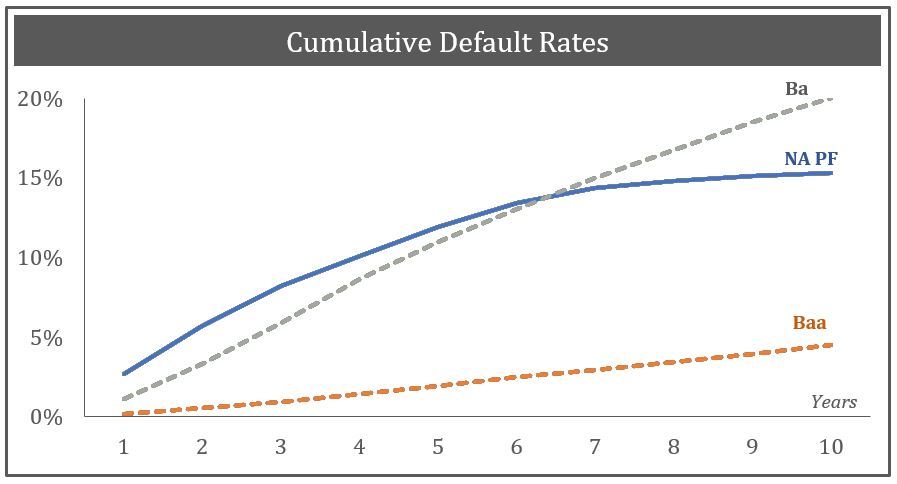

To many onlookers, since the great financial crisis, the world of fixed income securities has become an alien landscape. Yields on government bonds have fallen steadily across all developed markets. As the chart below reveals, there is now a record US$13trln+ of negative yielding fixed income paper, most of it issued by the governments’ of Switzerland, Japan and the Eurozone: –

Source: Bloomberg

The percentage of Eurozone government bonds with negative yields is now well above 50% (Eur4.3trln) and more than 35% trades with yields which are more negative than the ECB deposit rate (-0,40%). If one adds in investment grade corporates the total amount of negative yielding bonds rises to Eur5.3trln. Earlier this month, German 10yr Bund yields dipped below the deposit rate for the first time, amid expectations that the ECB will cut rates by another 10 basis points, perhaps as early as September.

The idea that one should make a long-term investment in an asset which will, cumulatively, return less at the end of the investment period, seems nonsensical, except in a deflationary environment. With most central banks committed to an inflation target of around 2%, the Chinese proverb, ‘we live in interesting times,’ springs to mind, yet, negative yielding government bonds are now ‘normal times’ whilst, to the normal fixed income investor, they are anything but interesting. As Keynes famously observed, ‘Markets can remain irrational longer than I can remain solvent.’ Do not fight this trend, yields will probably turn more negative, especially if the ECB cuts rates and a global recession arrives regardless.

Today, government and investment grade corporate debt has been joined by a baker’s dozen of short-dated high yield Euro names. This article from IFR – ‘High-yield’ bonds turn negative– explains: –

About 2% of the euro high-yield universe is now negative yielding, according to Bank of America Merrill Lynch.

That percentage would rise to 10% if average yields fall by a further 35bp, said Barnaby Martin, European credit strategist at the bank.

He said the first signs of negative yielding high-yield bonds emerged about two weeks ago in the wake of Mario Draghi’s speech in Sintra where the ECB president hinted at a further dose of bond buying via the central bank’s corporate sector purchase programme. There are now more than 10 high-yield bonds in negative territory…

The move to negative yields for European high-yield credits is unprecedented; it didn’t even happen in 2016 when the ECB began its bond buying programme.

During Q4, 2018, credit spreads widened (and stock markets declined) amid expectations of further Federal Reserve tightening and an end to ECB QE. Now, stoked by fears of a global recession, rate expectation have reversed. The Fed are likely to ease, perhaps as early as this month. The ECB, under their new broom, Christine Lagarde, is expected to embrace further QE. The corporate sector purchase program (CSPP) which commenced in June 2016, already holds Eur177.8bln of corporate bonds, but increased corporate purchases seem likely; it is estimated that the ECB holds between 25% and 30% of the outstanding Eurozone government bond in issue, near to its self-imposed ceiling of 33%. Whilst the amount in issues is less, the central bank has more flexibility with Supranational and Euro denominated non-EZ Sovereigns (50%) and greater still with corporates (70%). In this benign interest rate environment, a continued compression of credit spreads is to be expected.

Yield compression has been evident in Eurozone government bonds for decades, but now a change in relationship is starting become evident. Even if the ECB does not increase the range of corporate bonds it purchases, its influence, like the rising tide, will float all ships. Bund yields are likely to remain most negative and the government obligations of Greece, the least, but, somewhere between these two poles, corporate bonds will begin to assume the mantle of the ‘nearly risk-free.’ With many Euro denominated high-yield issues trading below the yield offered for comparable maturity Italian BTPs, certain high-yield corporate credit is a de facto alternative to poorer quality government paper.

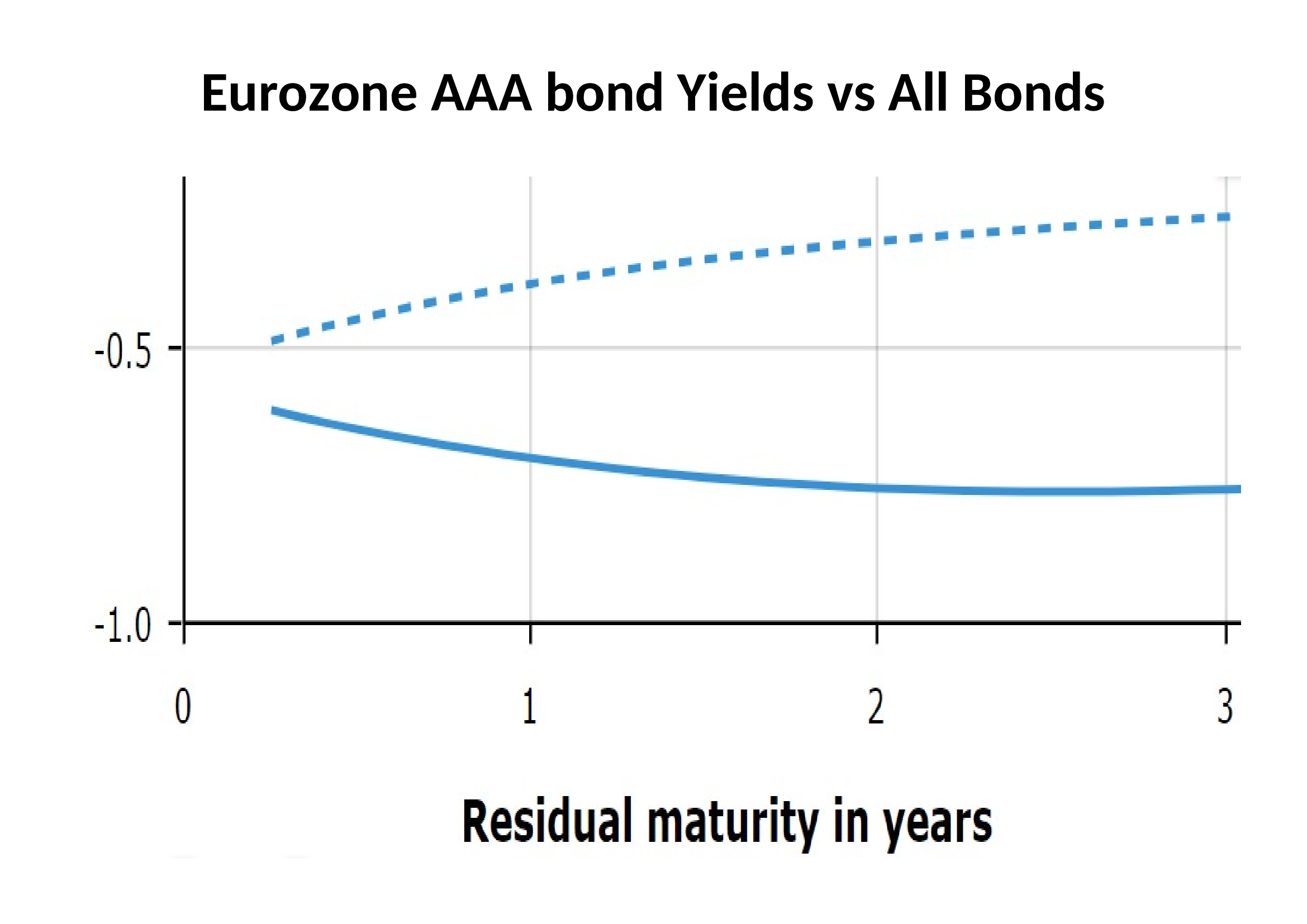

The chart below is a snap-shot of the 3m to 3yr Eurozone yield curve. The solid blue line shows the yield of AAA rated bonds, the dotted line, an average of all bonds: –

Source: ECB

It is interesting to note that the yield on AAA bonds, with a maturity of less than two years, steadily becomes less negative, whilst the aggregated yield of all bonds continues to decline.

The broader high-yield market still offers positive yield but the Eurozone is likely to be the domicile of choice for new issuers, since Euro high-yield now trades at increasingly lower yields than the more liquid US market, the liquidity tail is wagging the dog: –

Source: Bloomberg, Barclays

The yield compression within the Eurozone has been more dramatic but it has been mirrored by the US where the spread between BBB and BB narrowed to a 12 year low of 60 basis points this month.

Wither away the dealers?

Forgotten, amid the inexorable bond rally, is dealer liquidity, yet it is essential, especially when investors rush for the exit simultaneously. For corporate bond market-makers and brokers the impact of QE has been painful. If the ECB is a buyer of a bond (and they pre-announce their intentions) then the market is guaranteed to rise. Liquidity is stifled in a game of devil take the hindmost. Alas, non-eligible issues, which the ECB does not deign to buy, find few natural buyers, so few institutions can justify purchases when credit default risk remains under-priced and in many cases the yield to maturity is negative.

An additional deterrent is the cost of holding an inventory of fixed income securities. Capital requirements for other than AAA government paper have increased since 2009. More damaging still is the negative carry across a wide range of instruments. In this environment, liquidity is bound to be impaired. The danger is that the underlying integrity of fixed income markets has been permanently impaired, without effective price intermediation there is limited price discovery: and without price discovery there is a real danger that there will be no firm, ‘dealable’ prices when they are needed most.

In this article from Bloomberg – A Lehman Survivor Is Prepping for the Next Credit Downturn – the interviewee, Pilar Gomez-Bravo of MFS Investment Management, discusses the problem of default risk in terms of terms of opacity (the emphasis is mine): –

Over a third of private high-yield companies in Europe, for example, restrict access to financial data in some way, according to Bloomberg analysis earlier this year. Buyers should receive extra compensation for firms that curb access to earnings with password-protected sites, according to Gomez-Bravo.

Borrowers still have the upper hand in the U.S. and Europe. Thank cheap-money policies and low defaults. Speculation the European Central Bank is preparing for another round of quantitative easing is spurring the rally — and masking fragile balance sheets.

Borrowers still have the upper hand indeed, earlier this month Italy issued a Eur3bln tranche of its 2.8% coupon 50yr BTP; there were Eur17bln of bids from around 200 institutions (bid/cover 5.66, yield 2.877%). German institutions bought 35% of the issue, UK investors 22%. The high bid/cover ratio is not that surprising, only 1% of Euro denominated investment grade paper yields more than 2%.

I am not alone in worrying about the integrity of the bond markets in the event of another crisis, last September ESMA – Liquidity in EU fixed income markets – Risk indicators and EU evidence concluded: –

Episodes of short-term volatility and liquidity stress across several markets over the past few years have increased concerns about the worsening of secondary market liquidity, in particular in the fixed income segment…

…our findings show that market liquidity has been relatively ample in the sovereign segment, potentially also due to the effects of supportive economic policies over more recent years. This is different from our findings in the corporate bond market, where in recent years we did not find systematic and significant drop in market liquidity but we observed episodes of decreasing market liquidity when market conditions deteriorated…

We find that in the sovereign bond segment, bonds that have a benchmark status and are characterised by larger outstanding amounts tend to be more liquid while market volatility is negatively related to market liquidity. Outstanding amounts are the main bond-level drivers in the corporate bond segment…

With reference to corporate bond markets, the sensitivity of bond liquidity to bond-specific and market factors is larger when financial markets are under stress. In particular, bonds characterised by more volatile market liquidity are found to be more vulnerable in periods of market stress. This empirical result is consistent with the market liquidity indicators developed for corporate bonds pointing at episodes of decreasing market liquidity when wider market conditions deteriorate.

ESMA steer clear of discussing negative yields and their impact on the profitability of market-making, but the BIS annual economic report, published last month, has no such qualms (the emphasis is mine): –

Household debt has reached new historical peaks in a number of economies that were not at the heart of the GFC, and house price growth has in many cases stalled.For a group of advanced small open economies, average household debt amounted to 101% of GDP in late 2018, over 20 percentage points above the pre-crisis level…Moreover, household debt service ratios, capturing households’ principal and interest payments in relation to income, remained above historical averages despite very low interest rates…

…corporate leverage remained close to historical highs in many regions. In the United States in particular, the ratio of debt to earnings in listed firms was above the previous peak in the early 2000s. Leverage in emerging Asia was still higher, albeit below the level immediately preceding the 1990s crisis. Lending to leveraged firms – i.e. those borrowing in either high-yield bond or leveraged loan markets – has become sizeable. In 2018, leveraged loan issuance amounted to more than half of global publicly disclosed loan issuance loans excluding credit lines.

… following a long-term decline in credit quality since 2000, the share of issuers with the lowest investment grade rating (including financial firms) has risen from around 14% to 45% in Europe and from 29% to 36% in the United States. Given widespread investment grade mandates, a further drop in ratings during an economic slowdown could lead investors to shed large amounts of bonds quickly. As mutual funds and other institutional investors have increased their holdings of lower-rated debt, mark-to-market losses could result in fire sales and reduce credit availability. The share of bonds with the lowest investment grade rating in investment grade corporate bond mutual fund portfolios has risen, from 22% in Europe and 25% in the United States in 2010 to around 45% in each region.

How financial conditions might respond depends also on how exposed banks are to collateralised loan obligations (CLOs). Banks originate more than half of leveraged loans and hold a significant share of the least risky tranches of CLOs. Of these holdings, US, Japanese and European banks account for around 60%, 30% and 10%, respectively…

…the concentration of exposures in a small number of banks may result in pockets of vulnerability. CLO-related losses could reveal that the search-for-yield environment has led to an underpricing and mismanagement of risks…

In the euro area, the deterioration of the growth outlook was more evident, and so was its adverse impact on an already fragile banking sector. Price-to-book ratios fell further from already depressed levels, reflecting increasing concerns about banks’ health…

Unfortunately, bank profitability has been lacklustre. In fact, as measured, for instance, by return-on-assets, average profitability across banks in a number of advanced economies is substantially lower than in the early 2000s. Within this group, US banks have performed considerably better than those in the euro area, the United Kingdom and Japan…

…persistently low interest rates and low growth reduce profits. Compressed term premia depress banks’ interest rate margins from maturity transformation. Low growth curtails new loans and increases the share of non-performing ones. Therefore, should growth decline and interest rates continue to remain low following the pause in monetary policy normalisation, banks’ profitability could come under further pressure.

Conclusion and investment opportunities

Back in 2006, when commodity investing, as part of a diversified portfolio, was taking the pension fund market by storm, I gave a series of speeches in which I beseeched fund managers to consider carefully before investing in commodities, an asset class which had for more than 150 years exhibited a negative expected real return.

An astonishingly large percentage of fixed income securities are exhibiting similar properties today. My advice, then for commodities and today, for fixed income securities, is this, ‘By all means buy, but remember, this is a trading asset, its long-term expected return is negative; in other words, please, don’t forget to sell.’