Jim Grant, editor of Grant’s Interest Rate Observer, warns of the rampant speculation in the stock market. He worries that the central banks are underestimating the threat of persistently high inflation and explains why gold has a bright future.Christoph Gisiger08.11.2021, 01.29 UhrMerkenDruckenTeilen

The financial markets are «high». In the U.S., the S&P 500 is up for seven straight days, closing on another record at the end of last week. Particularly in demand are red-hot stocks like Tesla and Nvidia with fantastically rich valuations. Together, the two companies have gained around $600 billion in market value in the past three weeks alone.

For Jim Grant, this is an environment that calls for increased caution. According to the editor of the iconic investment bulletin «Grant’s Interest Rate Observer», investors have to beware of an explosive cocktail combining exceptionally easy monetary policy, a pronounced appetite for speculation, and the high degree of leverage. He also thinks that central banks are underestimating the risk of persistent inflation.

«The Fed reminds me of a speculator who is on the wrong side of the market», says Mr. Grant. The fact that the Federal Reserve is now beginning to taper its bond purchases makes little difference in his view. «It’s like pouring a little less gasoline on the fire,» he thinks.

In this in-depth interview with The Market/NZZ, which has been edited and condensed for clarity, the outspoken market observer and contrarian investor compares today’s environment with the second half of the 1960s and explains why he expects persistently high inflation rates. He explains what this means for the dollar as well as for gold, and where the best investment opportunities are with respect to the challenge of global warming.

Mr. Grant, what does the financial world look like from your perspective in late fall 2021?

It feels like the only days the stock market doesn’t make new highs is Saturday and Sunday when it’s not open. So certainly, there is never a dull moment. Things are very different, they are singular: We have the lowest interest rates in about 4000 years, or perhaps 3990 years because they have recently gone up a bit. But these are still some of the lowest interest rates on record. At the same time, we have some of the highest equity valuations with perhaps the exception of 1999 and 2000. And, we have one of the most speculative Zeitgeists on record. It is a time of disinhibition, of rampant, riotous speculation and of all the accompanying thrills and chills.

Few people know the history of financial markets as well as you do. What parallels would you draw to the current environment from the past?

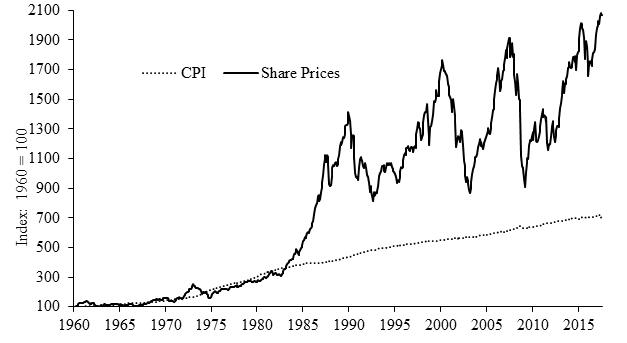

There are certainly some things that resemble it. For instance, the late 1960s anticipated some of this. It was a time of rising CPI inflation and a great boom in new issues and over the counter stocks. During that era, a writer who went by the pen name «Adam Smith» wrote popular books about Wall Street, including «The Money Game». He said what you have to do is to go out and hire some very young people to run your portfolios for you because only they understand what’s happening. I think of this in connection with the novelties of today: You want to go out and hire people in the age of perhaps 21 or 22 and give them each a million dollars as they go out and speculate without any pretense of security analysis. They just go out and buy all of the NFTs and cryptos that are going up.

Are there also specific differences from previous speculative bubbles?

I think today’s Zeitgeist is unique in the intensity of the speculation and in the amount of dollars, or Swiss Francs, British Pounds or Euros involved. And, it is perhaps unprecedented in the leverage applied to these speculations. But it is not unique in the sense that humanity, the human race in one great aggregate in its past and present, has lived through these episodes before. We have lived through them in the tulip mania of course, and the great speculation of the early 18th Century with the Mississippi Company and the likes, and the railroad bubble after that. Speculative episodes aren’t anything but unprecedented. So let me re-emphasize: What is unique today is the intensity, the amount of money, the amount of leverage and the monetary backdrop. All of these things are unique.

Where do you observe the biggest excesses when it comes to leverage?

I’m thinking of corporate leverage in particular. Just to pick one example, you can observe it in the decline in the quality of the debt as witnessed by the deterioration of the covenants; the fine print in the section of a bond indenture which limits the options or choices a corporate borrower can make with respect to adding new debt or distributing new cash. Today, the covenants are much weaker, and the ratio of debt to cash flow is much higher than it was even in 2007-08.

We know what happened next: The credit crisis almost caused a meltdown of the financial system. Nevertheless, today even long-term unprofitable companies are generously financed by investors like SoftBank with private equity and venture capital money.

Certainly, SoftBank is right up there as an exemplar or an avatar of the current age. It takes this place with Tesla, China Evergrande and with other companies. The way they operate to enhance themselves and the goals they have set for themselves exemplify a time of free and easy lending and borrowing as well as of flyaway prices and of seemingly limitless valuations.

At the same time, wild trading in short-term stock options is taking place. Is the stock price of companies like Tesla being manipulated?

I haven’t made any study between the connection of option trading activity and stock prices, so I have to decline to comment on that. But this is a time of unusually, if not uniquely easy financial conditions, and a time of conditioned expectations by repeated interventions of the Federal Reserve to contain any weakness in share prices and bond prices. As a general rule, in such a setting you would expect that people would be out over their skis.

At the moment, the most important question is whether the rise in inflation will be persistent or transitory. What do you think?

I’m in the persistent camp, rather than the transitory camp. But we’re all guessing, and it becomes ill for anyone to dogmatize or to insist that she or he knows the future. Especially, since we collectively have been so surprised by events like the pandemic. So it’s not as if anyone has a clear line of the future. But what’s so striking about the current alignment of the financial stars is that the bond market – either it’s foresight, hindsight or just faith – is choosing to look beyond today’s inflation problems.

What do you mean by that?

In the United States, the ten-year Treasury note is yielding more or less 1.5%, despite the measured rate of inflation being currently in excess of 5% year-over-year. And the increase in producer prices is even greater. So the bond market, like the Fed, is making a big bet on this notion of a transitory inflation that is all about the shortage of goods and services, rather than the excess of purchasing power.

Why do you think the Fed’s assessment of a transitory inflation could prove to be wrong?

Well, nothing is permanent in our transitory lives. But my hunch from examining current data and from recalling past instances of serious inflation is that this very well could be persistent. By that, I mean lingering well beyond the first few months of 2022, perhaps going on for a year, or two or three. Interestingly, there has only been one prior serious episode of a piece-time inflation. Every other inflation in U.S. up until the one that began in 1965, was a phenomenon of war or the aftermath of war.

How did inflation come about at that time?

The inflation that began in the Sixties crept in on little cat’s feet, to borrow from the poem «Fog» by Carl Sandburg. First, it was 3%, then 4%, and it didn’t seem too bad. But by late 1967, the then Chairman of the Fed, William McChesney Martin, said that it was too late: The horse of inflation was out of the barn. Today, people talk about the inflation in the Seventies, but we should not forget that it began in the mid-Sixties in a seemingly harmless way. Like today, many people said at that time that a little inflation is desirable because it lubricates the wheels of commerce and it makes people optimistic about the future because their nominal wages are going up. So the inflation came upon the world very gently and gradually, but before you knew it, it became entrenched.

Where do you see signs of similar developments today?

For instance, take a look at what’s happening at John Deere & Co. They are in the first major strike since 1986, and the Union membership voted down a wage package that looked like a rise of 10%. So we can’t predict the future, but we can observe how investors are setting the odds on the future – and from what I can tell, investors are betting on transitory inflation. They are betting that the central banks are in control, and that today’s low interest rates will prove persistent and that everything is more or less fine. That’s the consensus as one reads it in the marketplace. But I think that it is not a certainty at all, and one is advised to take out insurance on this big bet being dead wrong.

What else points to permanently high inflation rates?

There is a general move in Corporate America, and perhaps business people elsewhere to build in a margin of safety in the supply chains and in manufacturing processes. The current state of the world’s supply chains reminds somewhat of the valuations of the world’s securities: There is no margin of safety in the financial market place, and there has been very little margin of safety in the construction of supply chains.

And what does that have to do with inflation?

That’s one reason to expect that we are embarked on an inflation that may be a little bit stickier and longer lived than the authorities would wish or expect: There is a movement to so-called onshore manufacturing, bringing activity away from the seemingly well protected low-cost Asian centers from where seamless transportation could deliver parts and finished goods reliably and cheaply in the past. It’s a move away from that to bring things back to higher-wage areas. And, as I see it, people are at a much faster pace than in the 1960s reforming their expectations and adapting to what may prove to be a longer duration problem.

Then again, at the FOMC meeting last week the Federal Reserve reiterated that it does not expect permanently high inflation.

That to me is another sign that this is a bigger problem than they admit. The Fed reminds me of a speculator or an investor who is on the wrong side of the market. But even though the market goes into the unexpected and unauthorized direction and this speculator is suffering, he will not sell if he’s long, or not cover if he’s short. Basically, the Fed is saying: No, we’re right! The markets are wrong, just be patient.

For the first time since the outbreak of the pandemic, the Fed is now reducing its securities purchases somewhat. By next summer, the stimulus program should be completely wound down. Isn’t that a step in the right direction?

The tapering is just a way of the Fed saying «we are not tightening; we are loosening at a slower rate.» History will make of it what it will, that the Fed met this inflation by buying $120 billion of bonds and mortgage-backed securities per month. And then, history will scratch its head to figure why the Fed has chosen to meet that inflation after six or nine months – however you want to date it – by continuing to buy a lot of securities and turning those securities into dollars. It’s like pouring just a little less gasoline on the fire.

Yet, despite the unprecedented stimulus measures and the huge increase in government debt, the dollar has been surprisingly robust this year.

But the competition isn’t much in the world of paper currencies. In a world of vanishingly tiny rates, I guess many people observe that American interest rates are relatively robust. Still, one always has to take the market’s judgment with respect and difference. After all, it is the market speaking. Still, I wonder if the market has taken the full measure of the weakness of the current Biden administration and of the geopolitical stirrings coming from China and the particular risk to Taiwan. That’s why the dollar might be at risk for geopolitical nuisance as well as for reasons having to do with American inflation.

Intuitively, however, one would think that the dollar would trend firmer in the event of an escalation in the Asia-Pacific region. Don’t investors usually take refuge in safe haven assets like the dollar in times of crisis?

It could be. It worked in March of 2020, interestingly enough. But it wasn’t the way it worked in the 1970s. So a great deal depends upon the world’s perception of the United States’ geopolitical strength. And a great deal depends upon the course of American interest rates. It depends for example on whether the Fed is prepared to carry through on its now very preliminary program of being a little bit less easy. But what happens if the market, instead of continuing to go up, reverses course? The Fed might panic, as it has panicked in recent years. So if you have a fall in stock prices, the Fed could loosen its policy again – and that wouldn’t be so hot for the dollar.

How can investors best position themselves in this environment?

Well, let’s take a quick look again on the lay of the land: Stocks are near all-time high valuations, interest rates near all-time lows, inflation is percolating, leverage high, and the Federal Reserve still in partial denial. People are reaching for yield at acrobatic levels. Figuratively speaking, they climb on steep ladders, grasping for returns in the hopes of generating some income to meet the actuarial demand of pension plans or University endowments. This is a setup of great risk and oddly enough of a widespread denial that it is risky.

What does that mean for investors?

I think this juxtaposition of objectively great financial risk on one hand, and the collective attitude of madcap indifference to that risk on the other hand spells trouble. Now, people can say to me: «That’s all well and good, except you have been saying that for a long time, in fact seemingly forever, and yet things go up.» My answer to that is: Yes, correct. All that’s true and I don’t know when things go south. So at «Grant’s», we try to present ideas that have a margin of safety and that can offer people a chance to realize good returns even in the midst of the aforementioned troubles and risks.

What’s an example for such an investment?

«Grant’s» had an investment conference a few weeks ago, and I would suggest that people take a page from Will Thomson, one of the speakers. His point was that when you’re serious about the climate you shouldn’t pay heed to inherently backward-looking ESG scores. In other words: You should not be buying these ESG funds that own nothing except Apple, Facebook and other FAANG names. You’re not helping the world by doing that. Instead, you are helping the world when you invest in companies that aren’t inherently «green», but are becoming «green».

What kind of companies are we talking about here?

Will made this point very well. As an example of constructive greenifying, he identified RWE, which once was Europe’s largest coal-powered utility and now is one of its top producers of carbon-free electricity. He also presented a selection of companies that make the component materials for solar panels and wind farms. For instance, he thinks Siemens Energy is a premier play on the burgeoning growth in turbines, substations, hydrogen electrolyzers and other essential energy-infrastructure items.

It’s also no secret that you are a passionate fan of gold. What’s your take on the precious metal at the current time?

I love it with the same intensity that I am frustrated by it, which is considerable. That is a rather poetic expression of my opinion. So let me get you a more down to earth answer: Gold is unusual in that it is kind of outside this speculative whirlwind. Gold mining stocks are perhaps at all-time cheap levels with respect to the S&P 500. Whether it’s yield you’re talking about, or free cash flow, or price to earnings, or profit margins: Gold mining shares are perhaps as cheap as they have ever been against the broad market. So gold is a little bit of an island of indifference in a boiling sea of gambling and speculation.

When will gold shine again?

Gold is not what cryptos are, it’s not what NFTs are, it’s not what Tesla is. It is outside of a raging speculation and I think it will come into its own raging speculation when this great speculative episode, correctly called the Everything Bubble, bursts. But it’s not going to attract much interest as long as stocks are making daily new highs. So count me still bullish, but also very frustrated.

James Grant

James Grant is the founder and editor of «Grant’s Interest Rate Observer», a twice-monthly journal of the investment markets and a must read for financial professionals. A former Navy gunner’s mate, he earned a master’s degree in international relations from Columbia University and began his career in journalism in 1972, at the «Baltimore Sun.» He joined the staff of «Barron’s» in 1975 where he originated the «Current Yield» column. Mr. Grant is the author of several books covering both financial history and biography. His latest book, «Bagehot. The Life and Times of the Greatest Victorian», was published in July 2019. Mr. Grant is a 2013 inductee into the Fixed Income Analysts Society Hall of Fame. He is a member of the Council on Foreign Relations and a trustee of the New-York Historical Society. He and his wife live in Brooklyn. They are the parents of four grown children.