By James Anderson

The Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH) is often cited by economists, policy makers and intellectuals in their explanations for the causes of the Great Financial Crisis. The EMH posits that the market processes and reflects all the relevant information through prices. This leaves us only able to learn things from the market, rather than being able to tell it things. In short, it states that ‘the market knows best’, writes Robert Shiller in his Irrational Exuberance:

The efficient markets theory asserts that all financial prices accurately reflect all public information at all times. In other words, financial assets are always priced correctly, given what is publicly known, at all times. Price may appear to be too high or too low at times, but, according to the efficient markets theory, this appearance must be an illusion.

Thus it was believed that, as Mark Carney writes in his Value(s):

if a market is deep and liquid, it should always move towards equilibrium, or, said another way, ‘it was always right’. The policymakers have nothing to tell the market, they had only to listen and learn. If markets move sharply away from a range that seems appropriate, the policymakers must humbly admit that there must be something they are missing that causes the market ‘in its infinite wisdom’ to behave the way that it does.

The EMH, as well as a broader climate of pro-market economics, paved the way for a large deregulation in the financial and banking sector in the run up to the GFC. With the onset of the GFC, the plausibility of the EMH – and of free market economics more generally – suffered a great blow, as Krugman writes:

Few economists saw our current crisis coming, but this predictive failure was the least of the field’s problems. More important was the profession’s blindness to the very possibility of catastrophic failures in a market economy. During the golden years, financial economists came to believe that markets were inherently stable — indeed, that stocks and other assets were always priced just right. There was nothing in the prevailing models suggesting the possibility of the kind of collapse that happened last year. Meanwhile, macroeconomists were divided in their views. But the main division was between those who insisted that free-market economies never go astray and those who believed that economies may stray now and then but that any major deviations from the path of prosperity could and would be corrected by the all-powerful Fed. Neither side was prepared to cope with an economy that went off the rails despite the Fed’s best efforts.

‘Free market economics’ suffered a great blow, but, as we will see, for reasons unfounded. Steeped in intellectual error, many who believed in ‘free markets’ before the onset of the huge economic crisis of 2007/8 also suffered an intellectual one. Such a crisis of ideas was best encapsulated by Alan Greenspan who said in 2008: “something which looked to be a solid edifice, and indeed a critical pillar to market competition and free markets did break down and I think that shocked me. I still do not fully understand why it happened, and obviously to the extent that I figure where it happened and why, I will change my views.” However, after about 3 seconds of thinking, we can see that the theory of efficient markets – or, for that matter, as Krugman writes, the belief “that free-market economies never go astray” – is totally incompatible and in fact diametrically opposed to the existence of central banks.

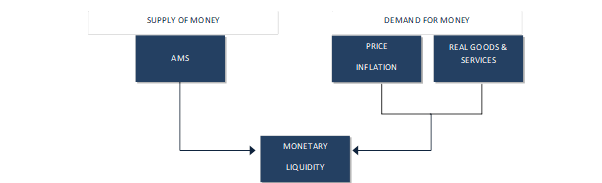

Central banks, through their monetary policy operations – as I explained in my earlier article for the Cobden Centre titled Central Banking, Knowledge and Unintended Consequences – arbitrarily control prices through changes to the money supply and to market interest rates. If Greenspan believed in the EMH or in free market economics more generally, then he could not simultaneously believe that monetary policy can work to achieve its mandated goals. If prices are always ‘right’ then how can Greenspan believe that fixing the most important price in the economy – the rate of interest – and manipulating all other prices through monetary policy is a wise policy choice? More pressingly, how can anyone possibly believe in the two simultaneously? Alas, this was/is the position of mainstream economists.

The two theories – monetary policy and the EMH – are mutually exclusive. As I hope to have shown above, due to the fact that all prices are constantly manipulated and changed in real terms by a political entity (the central bank), in no respect can one draw the conclusion that the ‘free market’ caused the Great Financial Crisis.

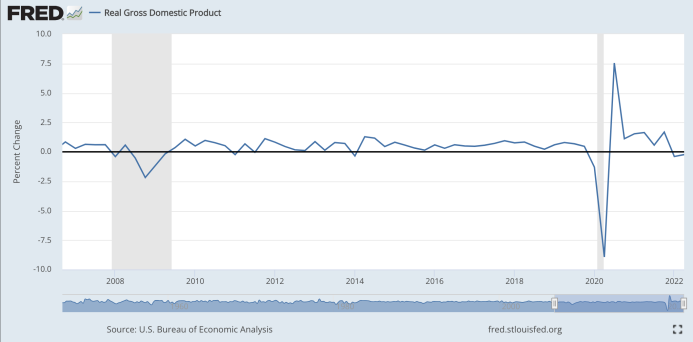

On the contrary, it was the very existence of the central bank and its underwriting and overseeing of great expansions of the money supply that caused the GFC, as explained by the Misesian (or Austrian) Theory of the Business Cycle. Alas, during and after the GFC – just like all the crises before it – mainstream economists, including Greenspan, supported global central banks’ unprecedented, unconventional and extremely powerful counter-cyclical monetary policy operations that intended to get the economy back to stability. Instead, such increasingly powerful monetary policy operations merely made inevitable a future crisis even larger, as well as aggravating existing socioeconomic ills that are driven by monetary inflation. Writes Gall, with his characteristic humour paired with deep insight:

Ominously, the Angry Upright Ape with the Spear is back again, more numerous and more grimly determined than ever, insisting on trying to achieve through Rage what can only be accomplished through Correct Perception, Analysis, and Appropriate Response

Central banks are trying to achieve by force – stronger and stronger monetary policy operations – what can only be achieved by a delicate and intricate knowledge of the economic system and of the government’s role within it. Until governments learn the great insights begot by Ludwig von Mises and F.A. Hayek, the future is one of further monetary inflation.

James Anderson is a recent Economics graduate from the University of Exeter and is currently writing a book with the working title: Monetary Folly: Intelligence is no Guarantee of Wisdom. He is looking to begin his career either in economic research or in finance after the completion of his book.

Exactly. And good luck with the book.

Trouble is doubt that those who need to read it (and this article) won’t.

Remember it is virtually impossible to get a man to understand something if his very livelihood depends on not believing it and / or believing the opposite.