As I expect many readers of this site will know, a debate has begun between the Austrian Economist Robert Murphy and the “Quasi-Monetarists” Scott Sumner, David Beckworth and Bill Woolsey. I encourage Cobden Centre readers to have a look at the contributions of both sides; both contain a great deal of insight, and unlike debates with Keynesians, this one is generally civil. My own view is a bit different to that of either side, but that’s not what I’m writing about here. Some commentators think that the argument can be resolved by looking at the “barrenness” of money. Unfortunately, life isn’t so simple.

Money is Barren

Money plays no direct role in satisfying human needs, for this reason the Classical Economists would say that money is “barren”. This is best explained with a hypothetical example. Consider a closed economy that uses only gold coins as money, perhaps an isolated island hundreds of years ago. Suppose that initially there was one ton of gold on the island; long ago all of it was mined out and made into coins. All of the prices on the island could be stated in ounces of gold. Then over time this economy grows and the wealth of the island’s inhabitants changes.

Now, suppose that instead of one ton of gold the initial stock had been two tons and again all of it was minted into coins. In this case would the development of the island’s economy have been different? Clearly prices would be different but that doesn’t mean that anything else would be. Money isn’t an input to any production process. Nothing is made out of money; each person receives money, keeps it for a while and passes it on. As Toby Baxendale often reminds us, wealth is only created when businesses make more or better goods and services. So the absolute amount of money isn’t important. For metallic money there are issues of practicality if coins must be very small or very large which can cause extra costs in handling money. But apart from that, nothing else can cause a difference between the path the economy would take with one ton and that with two. This barrenness applies to all types of money. It doesn’t apply to commodities that can be used to mint money, though. Gold isn’t barren since it’s an input into many industries. The use of money instead of barter confers many advantages on society, the lowering of transaction cost, for example. If the island had started out with no monetary economy then it would not have done as well, but if there is a monetary economy then money is barren in the sense described here. Mises explains all this in several places, for example in “The Theory of Money and Credit” p.238-239.

Monetary Fluctuations

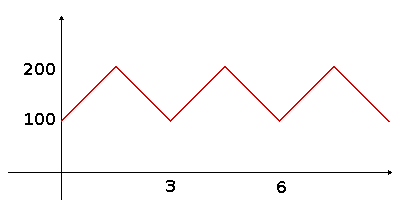

Fluctuations in the quantity of money are a more complex subject, as are fluctuations in prices and demand for money. The fact that money is barren doesn’t tell us everything we need to know. Let’s suppose that our island economy adopts a central bank and that it changes to using fiat currency rather than gold. The Central Bank decide on an unusual monetary policy. At the beginning of the first month the price level is 100. The Central Bank raise it to 200 by the end of the third month. They then make it fall back to 100 by the end of the sixth month. The Central Bank forces the price level to follow the graph below:

The Central Bank don’t tell anyone about their plan, they just start issuing new money at the beginning of the first month. What I want to ask here is: could this have no direct effect on the economy? The money that the central bank creates isn’t the input to any production process but its injection into the economy does change incomes and prices, and its subsequent withdrawal does too. In the previous example there was no proper change at all in the quantity of money. In the first case there was one ton of gold at the start and in the second there were two tons, but there was no transition between there being one and two. The examples were conceptually separate.

If monetary changes are very, very gradual we could expect little effect, but we can’t expect that if they aren’t. Roger Garrison gives a useful analogy here. Suppose that someone saws a plank of wood into pieces. The sawing may stir up sawdust into the air and make people cough, but once the sawing is done the dust will settle again. At the beginning when the plank is whole there won’t be any sawdust in the air, and all the sawdust will be on the floor soon after the cutting has finished. But, no one can prove that sawdust isn’t a problem by pointing to the time before the sawing and then pointing to another time afterwards.

Two Reasons for Changes: Price Changes and Redistribution

Redistribution is perhaps the most obvious consequence of money creation. If a government creates new money it can spend it as it likes, enriching certain groups while diminishing the value of existing stocks of money. Some economists hold that in an unhampered economy redistribution would be the only effect, though that redistribution would have negative consequences later. According to this view there would be no immediate fall in output. I would like the reader to look at the graph above and think about it using common sense rather than any economic theory they’ve learned. How could this “Monetary Policy” not cause chaos? And how could it not cause real output to fall soon after it began?

The issue here is that prices take time to change. This simple fact seems to cause an enormous amount of stress in discussions about economics. Some people call it “price stickiness” and say it’s a “market failure”. Others deny that price stickiness can occur in an unhampered economy. The only way that prices could change to immediately reflect all new information would be if every trade involved haggling. Thankfully, this isn’t the way things happen: when I buy a cup of tea in a cafe I don’t have to bid for it. One reason for this is that auctions are costly and changing prices is costly. Changing prices isn’t just costly in terms of physical resources; more importantly, it takes time for the entrepreneurs, managers and customers involved, time that may be better spent on other things. To some extent delays are cumulative: when a business input prices change it generally won’t change it’s output prices straight away, so if there are many stages of production a change will take longer to feed through.

None of this damages the argument against state support of Trade Unions. Cafes charge fixed prices for drinks because nobody would go to a cafe where they have to haggle. Jobs usually pay fixed hourly wages or salaries because employees prefer the security of those systems to piece-rate or other systems. Businesses that provide some stability in their prices may in many cases do better because of the predictability this provides to the customer and the cost saving to the business. All of the situations mentioned here are competitive. If more rapidly or more slowly changing prices would work better, then competition would provide them. But if a government supports a union, by banning employers from sacking striking workers for example, then they are tilting the scales of competition in order to benefit members of the union at the cost of everyone else.

What would happen if a Central Bank followed the policy above is that there would be a short lived boom at the beginning before everyone realises they have to increase their prices. Austrian Business Cycle Theory indicates that this boom would be unsustainable if it continued. But before it has a chance to get to that stage, the Central Bank starts reducing the price level, and then a bust will occur. The temporary boom occurs because prices can’t rise quickly and the bust because they can’t fall quickly. Neither will be beneficial and both will harm the economies ability to economize on scarce resources (On this see Mises’ essay “The Non-Neutrality of Money”).

Deflation

Money is said to be “non-neutral” because monetary forces can have an effect on output. Money isn’t a “veil”. Despite what Keynes wrote, most of the economists who studied the business cycle before him didn’t think that it was. If prices can have an effect on output then changes in both directions must have an effect, both price inflation and price deflation. If the crazy monetary policy described above would change output then so would any smaller, more normal change that occurs in real life. The difference is one of degree. Deflation, especially if it is large, can’t be exclusively good.

Some Austrian Economists believe that if there is deflation after a bubble of some sort has burst, then this provides “purging” and aids restructuring. I don’t agree with that theory, and it would take too long to go into that here. But what the analysis above tells us is that for deflation to be beneficial in this case, any benefits from the purging must outweigh the costs caused by the problems of deflation identified here.

To put it another way, if the creation of money to counteract a fall in prices causes misallocation and that’s a cost, then there are two costs to consider. The cost of that misallocation must be compared against the cost of deflation. No analysis is complete without accounting for both.

Great post.

The one ton or two ton “worlds” is a good example for monetary neutrality.

In the final few lines of the third of the above article, it says, “The use of money instead of barter confers many advantages on society, the lowering of transaction cost, for example.” But then it says in the very next sentence “If the island had started out with no monetary economy then it would not have done as well….” A blatant self contradiction!

“The use of money instead of barter confers many advantages on society, the lowering of transaction cost, for example.”

“If the island had started out with no monetary economy then it would not have done as well….”

I don’t see how these two statements are contradictory, the second follows from the first. Without a monetary economy transaction costs are higher and that makes economic development slower.

It seems to make perfect sense to me Ralph. Can you explain how exactly it is a contradiction?

In the article I’m using the meaning of “barter” in economics. Which is to exchange one good for another good, cows for pigs for example. Not the common meaning which is to barter or haggle with someone for a lower price.

My mistake. I overlooked the “not” in the second sentence. Doh!

Hi Current,

Great article.

Just on your final paragraph. I think Austrian economists might say that while the deflation is ultimately beneficial, the cost is the liquidation of failed projects, employees being laid off, losses being made by companies. This is not a pleasant process but this process must occur in order for the economy to heal.

This could be analogous to a fever when one is sick. Its not pleasant but this is the way the body heals from sickness.

To begin with I don’t consider myself to be against “Austrian economics” in general. I’m critical of some aspects of the theory of recessions. I’m much more critical of other schools of economics.

One of the things I don’t agree with is some of the ideas around purging.

Let’s go back to just before the housing bubble burst in the US. At that time prices, especially those of houses and fuel were rising. Many people realised that there they weren’t as rich as they thought they were. They acted accordingly by reallocating their spending. This is the shift in resources towards more near-term plans. As Mises says this is associated with a rise in the real interest rate. This is where we have the discovery of misallocations, projects that in the new economic climate are not worthwhile pursuing further. This can be called the “primary recession”.

But, at around the same time the environment of increased uncertainty causes people to demand larger holdings of money. I expect that people who worked in sawmills saw that their jobs became less safe and decided to retain more in their bank accounts. (I’m talking about demand for money-in-the-broader-sense here not just base money). This is a force in the opposite direction to that above. People who are worried about the future are saving more, the demand for money is rising. Quasi-Monetarists would say the “velocity of circulation” of money is falling too. There are some problems with this idea, but the essence of it is correct.

Now, in the central banking systems we have today the central bank controls the interest rate and heavily influences the quantity of money. What the Quasi-Monetarists argue, and I agree with them about this, is that in 2008 the Federal Reserve didn’t permit the quantity of money to grow quickly enough. That meant that readjustment had to take place through price changes, and since prices are sticky that caused further problems. This is the secondary recession. Steve Horwitz sometimes calls it “Wicksellian cumulative-rot”. What he means is that when the demand for money rises and it’s not satisfied then prices must fall, but they can’t fall quickly. So, there is a fall in output first, then as that happens uncertainty grows further and the demand for money rises further.

Now, what I’m concerned about is preventing the secondary recession. In my view between 2009 and at least a few month ago we were in a secondary recession. Or, at least, it was mostly secondary and only a little primary.

If the Fed had counteracted the rise in demand for money with a rise in supply then the recession would have been much shorter. Investments that are unsuitable for the rate of interest after the bubble would still have been liquidated. I’ll admit that this couldn’t have happened perfectly, the Fed could have raised the money supply too much and caused more unexpected inflation in the future. As it is I think many sound investments have been unnecessarily liquidated.

I seem to remember trillion dollar boosts in the money supply by the Fed in the USA during this period. A balance sheet that has never been so big with assets it has acquired via QE etc . This would seem to suggest that the Autro-Monetarist (latter day Hayek) call for an accomodation to an increase in the demand for money has failed, unless you think this was too little?

Looking at QE directly is looking at the quantity of reserves, not money-in-the-broader-sense. During the financial crisis because of exposure to loses or expected exposure banks drastically increased their quantity of reserves and decreased the amount of fiduciary media. There was a net rise in money supply but not as great as that some people indicate by looking at the QE figures.

During that period the demand for money rose drastically. That’s why there was price deflation. Velocity of MZM is an imperfect measure of money demand, it fallaciously associated money demand with GDP constituents. But I don’t think it can be ignored when it decreases by ~15% which is what happened over 2008-2009.

I don’t think the issue was the the Fed didn’t create enough money. In my opinion it had more to do with future expectations. The Fed didn’t make it clear that it would allow the money-supply to rise. A great deal of uncertainty is caused when the Fed aren’t clear about the path they’re going to take in the future.

In the UK there was actually a net fall in broad money after taking QE into account.

I’m not so familiar with the Fed’s programme, but IIRC, didn’t they target bank holdings of assets rather than non-banks as in the BoE’s APF?

Vimothy,

> In the UK there was actually a net fall in broad

> money after taking QE into account.

What do you mean? Which monetary aggregate fell? I wasn’t aware that any fell.

Anyway, I think the important thing is that demand rose very quickly. See the graph here:

http://www.marketoracle.co.uk/Article16059.html

> I’m not so familiar with the Fed’s programme, but

> IIRC, didn’t they target bank holdings of assets

> rather than non-banks as in the BoE’s APF?

To be honest I don’t know.

Sorry, slightly misremembered: broad money (M4) grew by less than the value of the APF programme (£8bn vs £200bn). In other words, if you remove QE from the equation (which directly increased broad money, since it targeted non-bank asset holders), money growth in the UK was negative.

I see, that sounds right.

Some Austrian School people like Jesus Huerta De Soto and myself (plus Mises – see Corrigan’s article of earlier in the week) would argue for a fixing of the money supply I.e. no money deflation. With a temporary

Friedman style agreed increase of say 2% PA, we can still keep people in their inflationist mindsets .

Fixing allows a more orderly re allocation of resourses to the better and stronger businesses rather than an uncontrolled bust .

Yourself and Huerta De Soto argue for no _monetary inflation_. Implementing that policy wouldn’t mean no price inflation or deflation. Prices would vary in the opposite direction to demand for money at a given time. Not all prices are affected to the same degree or at the same time, that depends on from which people they arise from. Because prices take time to change every sudden change in demand for money would affect output too.

The Mises article Sean Corrigan mentioned is actually the same one I mention above “The Non-Neutrality of Money”.

Mises point here is about price inflation not monetary inflation. He writes pretty much the same thing in “The Theory of Money and Credit” too.

In that article one of the paragraphs begins “To simplify and to shorten our analysis let us look at the case of inflation only.” Mises then describes the Cantillon effect. What he says in that paragraph applies to deflation too, the opposite of the case he describes occurs.

Yes, that is right. Under this enviroment, there cant be an evaporation of bank credit (money deflation) like we have now. What exists will still exist as it would be a physical thing. Then business survives by producing things people want and those that do not , go bust. This provides a more orderly setting that a “Lehman” style “fall off the edge of a cliff” moment with the terrible chaos that caused. I reflect more and more on this and think this is the better route forward and is a not a “liquidationist” Austrian style policy but something very pro-active and forward looking with regards to solving our problems.

Prices will move up , down, side ways and who knows where between goods in demand and not in damand . The point is, taking away the systems ability to deflate already granted credit at such rapid rates , irrespective of what individual prices are going / doing, if far more civilised a process of reckoning that we must eventually stop trying to wish away / postpone.

In some ways labelling some people Austro-Monetarists and Quasi-Monetarists is confusing. The view you’re taking here is very close to Friedman’s view in the 60s-80s. Friedman saw money quantity adjustments as a temporary ameliorative, he thought the long-term solution was the “Chicago Plan” to implement 100% reserve banking using fiat money.

The problem here as with your comment above is that the demand for money isn’t constant. For example, suppose the US had a constant money supply, and for some reason there was a large rise in demand for money. With a constant supply that can’t be serviced. If money demand rises sharply, think of the 15% fall in velocity I mentioned earlier, then supply can’t follow. Then due to sticky prices recession inevitably follows. Similarly, as I pointed out when discussing your plan, if demand for money falls then an ABCT boom will follow too.

I agree with this. I think that a totally inelastic supply of money would produce the exact opposite of price level stability, because the “price” of money would then bounce up and down with every change in demand.