TB: Tim Price is a fund manager who has a very good grasp of economics and certainly is Austrian-aware and supportive. Like many who buy the FT, I get it for the factual reporting on news, which is first class, but its editorials are terribly mainstream, dull, and often wrong. It’s a shame that more of Tim’s letters to aren’t published. If seen by our political masters, they would serve us all, and Lady Liberty, very well.

“God! How men of letters are stupid.” – Napoleon Bonaparte.

Since the financial crisis slowly wove itself into the popular consciousness, we have tried, on occasion, to highlight our own hopes and fears via that tried and tested monitor of the financial commentariat’s blood pressure, the FT letters page. Not all of the following submissions were published. In fact so very few of them made it, the simple, hopeful act of their conveyance resembled nothing so much as the opening day of the Battle of the Somme. We (re)publish them here so that they can be shared for posterity and savoured on those vast sunlit uplands that will play host to random financial chatter once the current crisis abates. If it ever does.

10 October 2007:

Sir,

Peter Cave (Letters, October 3) contributes to the debate over the “unjustness” of inheritance tax which has occupied many recently. On the basis that taxation consists of plucking the maximum amount of feathers from the goose with the minimum of hissing, one has to question whether a tax that contributes such a paltry amount of revenue to the exchequer will outlive such justifiable indignation from Middle England.

Many taxpayers might question the “justness” of the government stealing a portion of their capital gains from property, a theft the (im)morality of which is compounded by being inflicted on the dead, and which may result in the original property being forcibly sold. I would suggest that inheritors are “more deserving” than any bureaucracy, and “the lucky result of property value increases” is irrelevant to this debate.

If inheritance tax amounts to a tax on rising real estate values, will the government write cheques to inheritors when house prices enter a protracted fall?

27 June 2008:

Sir,

John Kay (“The strange financial physics of the inverse bubble”) invites readers to nominate new coinages to define the opposite of a bubble. If the outcome is simply a bear market, it is a “gribble”. If it is something altogether worse, dragging down sentiment towards financials, stocks and bonds, and provoking all forms of both inflationary and deflationary angst, it is a “deflobble”. If, in extremis, it turns out to be the infamous 25-standard deviation event that triggers the apparent end of life, the universe and everything in our fragile, globalised world, it is probably a “bank share”.

28 February 2009:

Sir,

Am I alone in finding the government’s harrying of Sir Fred Goodwin morally reprehensible? [With hindsight: probably, yes.] Or merely outrageously hypocritical?

Gordon Brown’s desperate attempts to claw back the former Royal Bank of Scotland chief’s pension entitlements are a disgusting reminder of the inevitable pandering to which politicians fall prone. I expect elected politicians to defend contract law, not to try and drive a coach and horses through it, no matter how righteous the public’s indignation. Such venal appeals to the mob (and Vince Cable, shame on you) will set a dangerous precedent, not least for MPs who happen to enjoy particularly luxurious pension provisions, whether those MPs are fit for purpose or not.

Perhaps former senior executives of the Financial Services Authority will also now be encouraged to return part of their entitlements – this mess, after all, happened on their watch, too. But politicians currying favour with the lowest common denominator should appreciate that those who live by the wobbly sword of public opinion can also die by it. And if the government’s intentions were to foment as much social unrest as possible in these difficult times, it seems to be going the right way about it.

8 May 2009:

Sir,

Congratulations to Toby Hamblin (Letters, May 7) for following in the wake of the European authorities by excoriating short sellers during the financial crisis. Perhaps he would like to close the stock markets altogether (no doubt the regulators gave some thought to that contingency). Pointing the finger at short sellers, real or presumed, after a market panic is always a popular pursuit. It does, however, ignore the iron truth that for every seller there has to be a buyer on the other side of the trade. Selling short is also a high-risk strategy: putative gains are limited to the differential between the spot price and zero; losses can be theoretically infinite.

Denouncing short sellers has become inextricably bound up with a general fear and distrust of hedge funds and alternative asset managers in the popular psyche. I would be grateful to any FT reader who can identify a hedge fund that has required extraordinary taxpayer support to carry it through a crisis that was caused by the malinvestment perpetrated by banks. If selling short is immoral and “painful” for the rest of humanity, how to describe the colossal leveraged purchasing and trading of toxic rubbish with what amounts to other people’s money?

28 May 2009 (tragically unpublished):

Sir,

Am I alone in finding Lex’s analysis of a deteriorating government bond market increasingly schizophrenic? As Treasury yields spiked higher, “Bond fears” of May 25 gave us “a terrifying glimpse of the nightmare scenario”. And then “Treasury sell-off” of May 27 gave us “..investors should relax a little”. Should we be spooked, or not?

Objective analysis of the dire state of Anglo-Saxon public finances indicates that we should be afraid. Very afraid. International investors are going to have to fund many trillions of dollars of debt over the next several years. And while Lex cites the Japanese success at raising debt financing despite a credit downgrade in 2001, Japan at the start of this decade was a special case. This time round, massive government indebtedness and fiscal incontinence is an almost ubiquitous international problem.

US Treasury and UK Gilt yields are rising for a very obvious reason: supply. Lots of it. Well into the future. So investors are right to be losing a little sleep at the potential funding problems of multiple western administrations, all overstretched and desperate to raise capital at exactly the same time. Not everyone trapped in this room necessarily gets out alive. The fact that the likes of Brazil and China seem increasingly keen to reduce their dependency on the US dollar is just one more reason for investors to question any relaxed stance to the parlous nature of western government finances. The banking bail-out, like the credit bubble that preceded it, was funded on the never-never. The bond vigilantes appear to be reminding us that there is no such thing as a free lunch.

23 July 2009:

Sir,

While it is right to encourage healthy debate about the role of future regulation in the City of London, I am not sure that Tom Brown is necessarily justified in some of his criticisms of the Bank of England (Letters, July 22).

The Bank was surely under no obligation to prevent the implosion of either Barings (through lack of risk management – sounds familiar?) or BCCI (through fraud).

Indeed, the collapse of these two firms almost makes one long for a more innocent age when banks could be allowed to fail rather than impose involuntary systemic costs on the rest of us.

As to the likelihood of the Bank attracting a sufficiently experienced and qualified staff, this gets to the absolute heart of the problem. Short of receiving infinite remuneration, no regulator will ever realistically be able to compete with the so-called “talent” on Wall Street and the City, even if that talent amounts to self-enrichment rather than wider wealth creation.

Since the playing field between regulator and regulated will never be entirely level, it might be more realistic to try and reintroduce a culture wherein caveat emptor holds more sway, and in which banking organisations that do stupid things can be allowed to go bust in an orderly manner without sacrificing taxpayers and government finances in the process.

22 October 2009 (tragically unpublished):

Sir,

Your Lex columnist (“Glass-Steagall redux”, October 22) appears to be in thrall to the political class. Both Northern Rock and HBoS are cited as apparent proof that reviving Glass-Steagall, a late and much lamented US act that separated commercial from investment banking, would have been of little use during the financial crisis. Northern Rock, as a fringe player in the mortgage market, was surely saved because it was politically expedient to rescue a business based in a Labour constituency. HBoS was forcibly merged into Lloyds with no less a financial mastermind than Gordon Brown acting as officiate and cheerleader. The decision to let Lehman Brothers fail was inherently political as much as regulatory – hardly surprising when its competitor Goldman Sachs, whose profits do not seem to have suffered unduly from the collapse of a major rival, has managed to insinuate itself into every part of the US administration.

Lex suggests that it is bad for the City for Mervyn King, who favours some form of return of Glass-Steagall, to be out of step with the government, the FSA and other regulators. Given that the worst banking crisis in living memory occurred on the latter’s watch and under their supposed oversight, I can think of no finer endorsement for Mr. King’s views. What is bad for all of us is a political system that capitulates to banking interests over those of taxpayers and, in the case of the US, allows financial lobbyists effective control of public spending. Greedy and incompetent bankers may be at the heart of this crisis, but venal politicians are not exactly far behind them.

13 November 2009 (tragically unpublished):

Sir,

Lex has a long and inglorious history of rubbishing gold but his latest critique “Peak gold?” (November 13) is more than usually wide of the mark. We are told that this precious metal is “Rare.. and immune to corrosion”. Quite true, in contrast to the fiat currencies, most notably of the Anglo-Saxon variety, that are currently being printed as if they were going out of fashion, which of course they are. Those paper currencies might fairly be described as the opposite of rare, and their values notably prone to the corrosive influence of politicians.

To say that psychology rather than supply and demand is responsible for the recent surge in the gold price is somewhat baffling. When demand for a finite product outstrips supply, its price rises, whatever the perceived popular mood. And to suggest that gold is “almost always just being held in order that it might later be sold, to a greater fool” is to describe all speculation through the ages in all its forms.

At a time when all risk assets seem to be rising in price, it would be dangerous to highlight just one – gold – as a special case. But perhaps the gold price is rising precisely because the “modern currency” that Lex so venerates is falling rapidly into disrepute and individual, institutional and sovereign investors, not entirely foolishly, are seeking to protect their wealth in a superior store of value. As a wise friend recently reminded me, at any given time gold may or may not be a good investment, but it is always money.

8 November 2010 (tragically unpublished):

Sir,

It was a very cruel joke to publish Richard Barwell’s recent letter (“Exit from first round of QE now seems premature”), particularly as it followed hot on the heels of Fed chairman Ben Bernanke’s announcement of so much more of the stuff. It was certainly a delicious coinage of Mr Barwell’s to suggest that this argument “makes no sense in theory”. This reminded me of those scientists who also contend that bumble bees cannot fly – in theory.

Can I suggest that the FT letters page imposes some kind of moratorium on self-interested and highly conflicted “advice” from an academic school – economics – that having brought us to the brink, is now in danger of theorising itself into total absurdity? To read that Mr Barwell is employed by the one organisation that has done more than any other to destabilise if not destroy the UK financial system – RBS – was the icing on this particularly ironic cake.

QE does nothing more than put yet more capital into the hands of bankers who can then either play in the markets with it, or sit on it. In doing so, it also devalues its practitioners’ currencies versus those of regimes that have fundamentally sound economic policy. If our government and central bank wanted to do something properly constructive with all this newly created money, perhaps it could invest it into our country’s jaded infrastructure, rather than inflating further asset bubbles, the “wealth effect” of which is likely to be wholly illusory.

12 January 2011 (tragically unpublished):

Sir,

We have been playing the blame game for three years now in the aftermath of the banking crisis, and so far the debate has generated a lot more heat than light. This is probably because most commentators have taken a fragmentary (e.g. “it’s the fault of greedy bankers”) rather than a holistic view. In the interests of stating the obvious, politicians have played their own part in this mess – regulators were political appointees, and all connected parties failed to conduct sufficient oversight or control of the banking system. It is certainly breathtaking to see Labour attempting to score points off the current Chancellor, when it was the last Labour administration – the one that apparently saved the world – that wrote our failing banks a blank cheque in return for, erm, apparently no say whatsoever in terms of the management, strategy or remuneration policy of those businesses they took into effective state ownership. Has any government ever negotiated a worse outcome for its citizens?

There is a bigger problem, and one that badly impacts on all savers and investors globally. Fractional reserve banking amounts to a giant Ponzi scheme, perennially prone to crises of confidence, or in other words bank runs. Central banks under a fiat currency regime can and do

print money at will, at essentially no cost. The combination of fractional reserve banking and unsound, dishonest money is inherently inflationary, whatever central and commercial bankers say or do, thus effectively stealing wealth from those who work hard to create it. This is just one reason why much disparaged gold and silver as “natural money” are returning to prominence in a flawed monetary system. In the words of Jörg Guido Hülsmann, who has literally written the book (“The Ethics of Money Production”) on our dishonest monetary infrastructure, the main reason monetary institutions such as central banks were created was to “allow an alliance of politicians and bankers to enrich themselves at the expense of all other strata of society.”There is an alternative, and it is a return to sound money and honest, fully reserved banking. That would, of course, be less personally profitable for our casino bankers but much less costly for the rest of us. Our politicians now have an opportunity to demonstrate that they are not in the pocket of the banking lobby. I will not be holding my breath.

28 March 2011 (tragically unpublished):

Sir,

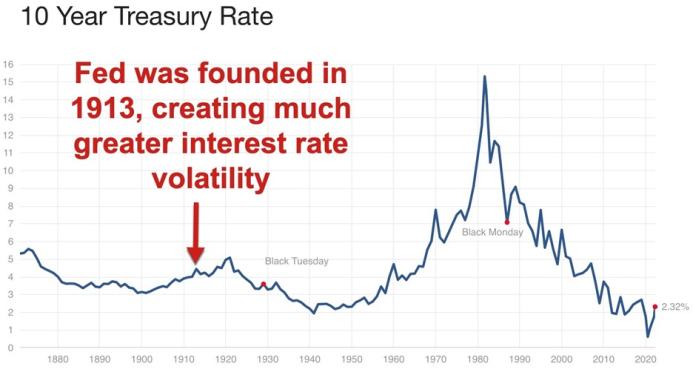

David Beffert (“Fed is better than gold bug solution”, March 28) asserts that the US Federal Reserve is better placed than gold to address what he terms “standard macroeconomic problems”. He is to be congratulated for cramming at least two tired old clichés, “gold bug” and “barbarous relic” into his statement, which is not so much an argument as an expression of personal opinion unsupported by any evidence. Some of your readers may, however, take issue with the suggestion that the problems facing the US economy, and its currency, are merely standard and macroeconomic, whatever that is supposed to mean. I would suggest that the problem is severe and existential, inasmuch as it amounts to a growing lack of confidence in the US dollar, and in a government debt market that objective observers might regard as resting on a bed of nitroglycerine. My understanding is that the US Federal Reserve, far from being “an independent central bank”, is effectively a private banking cartel, the chairman of whose board of governors is appointed by the President. That stretches the definition of independence somewhat, but credit to the Fed for having done such a bang-up job on its core purpose, the pursuit of monetary stability and full employment. I notice that Mr Beffert is from Washington, DC. He obviously nurses no political agenda in his knee-jerk condemnation of gold as a store of value, versus for example the US dollar, whose purchasing power has fallen by over 90% during the last century. The term “paper bug” might be appropriate.

26 August 2011 (tragically unpublished):

Sir,

Rod Price is a good advocate for bad banks (Letters, August 26) when he defends inflation as “a less painful way for savers, i.e. lenders, to take their losses”. I doubt whether many of your retired readers would share his casual attitude to the malign influence of inflation upon a fixed savings pot. I note that in the same edition of the FT Japanese equity spokesperson Peter Tasker is wheeled out to rubbish gold. Yes, the gold price can be volatile when expressed in terms of a depreciating and essentially worthless paper currency. It remains to be seen whether gold will be as good a store of value as Japanese stocks, which have lost three quarters of their value over the last twenty years. But state sanctioned inflation is most certainly a theft, and one that rewards financiers and the feckless at the expense of the prudent. And as the noted Austrian economist Ludwig von Mises pointed out, “Inflation can be pursued only so long as the public still does not believe it will continue. Once the people generally realize that the inflation will be continued on and on and that the value of the monetary unit will decline more and more, then the fate of the money is sealed.” For a financial publication, your attitude towards sound money is bizarre.

Comments are closed.