A common interpretation of the credit crunch and ensuing global turmoil is that it was all down to unregulated or under-regulated financial institutions and markets. As a result, one of the most commonly advanced solutions is for more and/or better regulation. Indeed, this call is about as close as we get to a firm demand from the presently fashionable ‘occupy’ protests.

There are many things wrong with this view. First, the underlying causes of the recent boom and bust could be found, as so often, in monetary disturbances. In comparison to the damage wrought by a deluge of credit, any regulatory deficiencies are just hundreds and thousands atop a cake that was always going to turn out pretty sour.

Secondly, nothing says ‘profit opportunity’ to financial institutions quite like some new financial regulation. To give just one of countless examples, the Eurodollar market sprang into life thanks to attempts like Regulation Q to impose limits on interest rates. The financial innovators will only ever be one step behind the regulators for as long as it takes them to read the regulation. Then they streak ahead.

And thirdly, it is a mistake to think that financial markets were notably under-regulated. After redesigning British financial regulation almost from scratch, the Labour government never ceased tinkering with it. As Terry Arthur and Philip Booth wrote recently (PDF)

To obtain permission to carry out regulated activities an organisation must meet certain qualifying conditions. These include having adequate resources (financial resources as well as internal systems and procedures). The conditions are laid out in the FSA’s Integrated Handbook…Regulation is bureaucratic in the extreme. It is no longer possible to determine the number of pages in the handbook, but an indication is given by the following example. There are ten main sections in the book. One of those main sections…is that on ‘Listing, prospectus and disclosure’. This contains three subsections which have between nine and 23 sub-subsections each. Taking one of those sub-subsections, under the ‘Listing rules’, there are six sub-sub-subsections

Fortunately we can look at the economic impact of regulation worldwide with the release by the International Finance Corporation of the World Bank of its annual ‘Doing Business’ report which compares regulatory environments and the ease of doing business across countries. The reports message is unequivocal; regulation is mostly bad and those calling for more of it are calling for economic suicide.

A report on the report by The Economist picked out some notably egregious examples

A typical company in Congo with a gross profit margin of 20% faces a tax bill equivalent to 340% of profits…How long, for example, does it take to register a company? In New Zealand it takes one day and costs 0.4% of the local annual income per head. In Congo it takes 65 days, involves ten steps and costs 551% of income per head…Other procedures the IFC measures include registering a property (which takes one day in Portugal, 513 in Kiribati); obtaining a construction permit (five steps in Denmark, 51 in Russia); enforcing a simple contract through the courts (150 days in Singapore, 1,420 in India); and winding up an insolvent firm (creditors in Japan recover 92.7 cents on the dollar, those in Chad get nothing at all)…A young entrepreneur in Liberia who builds a new warehouse must wait on average 586 days to connect it to the power grid. In Ukraine it takes 274 days; in Germany only 17. Guess which of these countries has a thriving manufacturing sector?”

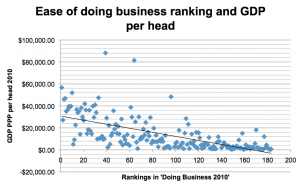

The chart below illustrates the point

Source: ‘Doing Business 2010′ (PDF) and International Monetary Fund ‘World Economic Outlook Database’ – Puerto Rico, Palau, the Marshall Islands, Micronesia and West Bank and Gaza are omitted for lack of a comparable data point

We see that while a light regulatory environment is not a guarantee of wealth, it is a necessary precondition. Not surprisingly, The Economist sees a causal relationship

Cutting red tape makes countries richer, if the 873 peer-reviewed articles and 2,332 working papers that use the “Doing Business” data are anything to go by. A study in Mexico found that simplified municipal licensing led to a 5% increase in the number of registered companies and a 2.2% increase in jobs. It also lowered prices for consumers. Bankruptcy reform in Brazil caused the cost of credit to fall by 22%. Countries with flexible labour rules saw real output rise by 17.8% more than those with rigid ones”

Calls for more regulation are both pointless and dangerous; pointless in that it won’t solve the undoubted problems in our present economic system and dangerous in that it could end up making us even worse off. More regulation is not the answer.

Related articles

- Europe’s underground economies by David Howden, 7 November 2011

- Financial regulation and the deception of government intervention by Steve Baker MP, 1 June 2011

- The kindness of geniuses by Jamie Whyte, 14 January 2010

You seem to jump from financial regulations to general regulations.

However, if you want to talk about general regulations……

The secret is not to try and make the Congo like New Zealand – it is not try and speed up the granting of licenses and permits.

The only way to really help desperatly poor countries like the Congo is to ABOLISH licenses and permits – not try and make the administors work faster (the Economist magazine approach), but get the govenrment administrators out of the way.

As for financial regulations.

The reason that people think that banks (and other such) are a special case is the feeling people have that bankers create money – from nothing.

And it is not just a feeling – it is (for a period of time anyway) a fact.

To deal with just one banker book keeping trick.

When a banker lends someone money they often do NOT transfer money from a real saver to a borrower – they just “credit to the account” of the borrower money they have just “created” (via the stroke of a pen – or pressing a few keys on computer).

Whilst the credit/money bubble lasts – this will indeed be “new money” that the banker has created (from nothing).

This is why “broad money” (bank credit) gets out of line with “narrow money” (the monetary base – the actual currency) and boom/bust events occur.

This is why, in the 19th century (when such things were better understood than they are today) people used to say “free trade in banking is free trade in swindleing”. And the abuses of bankers then were tiny compared to what is done today.

However, regulations will not solve it – after all the banks are already buried alive in regulations both national and international (Basel One, Basel Two, Basel Three).

So why did the vast inverted pyramid of debt (of credit money) form if banks are controlled (in almost every detail) by governments?

As John Phelan knows – there is no contradiction here.

Governments (both Central Banks and elected governments) WANTED the vast increase in the credit money supply.

They thought it was an easy road to prosperity.

And to judge by their comments “we must get lending going again” (i.e. loans that are not from real savings – as real saving is at all time low), “we must keep up the value of homes” (i.e the credit bubble “value” of homes), governments still want easy prosperity from monetary expansion.

They have learned nothing.

I would have thought regarding banks, there’s a good case to be made for greater regulation of OTC derivatives. Nobody objects to the fact that, for instance, we trade stocks, bonds and futures through formal exchanges and clearing houses, with certain government reporting requirements (such as COT reports, quarterly income statements, etc). Given that derivatives form such a large part of banks’ balance sheets, I’d have thought much greater transparancy in these markets should be required.

Today’s monetary catastrophe would appear to have two causes:

Central Bank malfeasance & Regulatory Impotence

Private Banks created liquidity ex nihilo by “securitization”: a toxic alphabet soup of swaps and securities where private banks increased the money supply by converting more and more real assets into tradable instruments. (A new species of paper currency as it were.)

Central Banks then erred by then creating enough fiat currency to keep private banks liquid when in fact they were insolvent.

The job of the both BIS & FSB were supposed to provide good governance such that Private Banks would not fall into the temptation of the tragedy of the commons squared while Central Bankers were to be constrained from repeating Br’er Rabbit’s struggles with the Tar-Baby in some perverse version of monetary “mission-creep” (such as Greenspanian Puts)!

Paul Volcker as a central banker heroically rescued America from immanent Weimarian-Hyperinflation resulting from (among a myriad of causes) Nixon’s coerced unfettering of the American Greenback from gold – aka the barbaric relic.

Perhaps Volcker’s greatest achievement was Basel I, designed to prevent future Central/Private Bank collusion to ever again destroy the value of money. Banksters promptly (and with the usual connivance of their bought and paid for stooges in governments) responded with the misbegotten Basel II, to deliberately unravel Volcker’s prescient strictures of Basel I. (Correct me if I am wrong)

Now we witness in dismay an eviscerated Basel III with its incongruous shadow of the former Volcker rule; all still-born. Just ask Volcker himself!

So as a naive dilettante I pose the question: Conceding, all the while, the ill effects of Poor Governance – is it still not reasonable that “Good Governance” as opposed to “No Governance” is the order of the day?

I must be getting something wrong! I would be grateful for any response, for to tell the truth, I am most perplexed!

“You seem to jump from financial regulations to general regulations”

As thats not a distinction those calling for more “regulation” make I didnt make it either.